Latest News

Mapping the Sphinx

The details of mapping the Sphinx

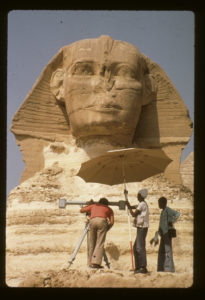

Ulrich Kapp and assistants talking stereo-pair photographs of the Sphinx with the photogrammetric camera.

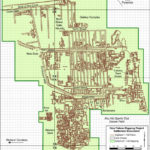

Why map a statue? There is no way to understand a monument as complex as the Sphinx without examining in detail of all of its elements. This includes mapping the bedrock of the Sphinx, mapping the ancient and modern restorations, and mapping the associated temples in the Sphinx complex.

While clearing the Sphinx quarry down to bedrock for a subsurface mapping project, Zahi Hawass and Mark Lehner noted that there were ancient deposits that had never been excavated. Using modern archaeological methods, the team revealed cultural material from the time of the pyramids, including numerous pieces of 4th Dynasty pottery (2575-2465 BC), right up through the Roman occupation of Egypt (30 BC-395 AD).

During the work, Hawass and Lehner realized that the existing maps of the Sphinx were not very useful and that, in fact, there were no accurate maps of this important monument.

AERA’s story began with a project to map the Sphinx, with Dr. James Allen as Director and Mark Lehner as Field Director. Sponsored by the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) over a five-year period, the ARCE Sphinx Project produced the only existing large-scale maps of the Sphinx.

Intent

Sunset at the equinox suggests intentional alignment

The alignment and iconography of the Khafre monuments suggest a strong connection to the cult of the sun god, Re.

One of the significant alignments discovered during the Sphinx mapping project is that a line can be drawn from the Sphinx Temple’s east-west axis through an enigmatic box along the right side of the Sphinx. The line continues to the apparent south side of Khafre’s pyramid as it appears on the horizon when viewed from the Sphinx Temple.

Twice a year, on the equinoxes, the sun sets on this alignment and would have illuminated the Sphinx Temple sanctuary and cult statue if the builders had finished the temple interior. The setting sun would renew the power of the dead king and like him, enter the underworld where Re and Osiris are united.

The Sphinx’s alignment with the other Khafre monuments indicates a building program linked to beliefs around a solar cult.

Auguste Mariette made a small note during his excavations at the Sphinx in the 1850s that he had found a shattered statue of Osiris at the base of the Sphinx box.

Restorations

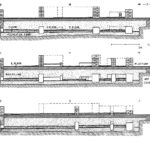

The southern elevation of the Sphinx as of 1979, produced by Ulrich Kapp of the German Archaeological Institute, with the masonry veneer color-coded by period by Mark Lehner.

Given the poor quality of the limestone from which the Sphinx’s lion body is cut, it’s not surprising that after many centuries the statue needed restoration, beginning in antiquity. Repair work began thousands of years ago and has continued throughout the statue’s history. Stone blocks of varying size have been used to encase the native rock of the Sphinx to restore its shape and protect it from further deterioration. The Roman restoration consisted of small brick-sized stones, which can still be seen in places. The Romans, however, used relatively soft white limestone that deteriorated badly.

The French engineer, Emile Baraize, carried out major excavations from 1926-1936. Baraize had reset much of the Roman stones that he found tumbled. Unfortunately, his 11 years of work were never published and many phases of architecture around the Sphinx were dismantled without proper documentation.

The soundest ancient restorations were those by the ancient Egyptians, who generally used durable masonry that developed a protective brown patina.

Looking between the forepaws of the Sphinx provides clues that help date the oldest repairs of the giant statue. There stand the remains of a small open-air chapel built by Thutmose IV. The centerpiece of the chapel’s back wall is a 15-ton stela dated to 1401 BC: the famous Dream Stela.

The Dream Stela commemorates Thutmose IV’s accession to the throne by relating a story of his path to kingship. He tells of a day as a young prince (not the crown prince) when he was hunting in the vicinity of the Sphinx and napped in the shadow of the statue’s head.

The Dream Stela

While he slept, the Sphinx, as the embodiment of the sun god, appeared in a dream and offered the throne of Egypt if Thutmose would clear the sand from around the statue’s body.

The Dream Stela offers compelling evidence for dating the oldest restoration work to Thutmose IV, about 1,100 years after Khafre built the Sphinx. The limestone blocks framing the stele are consistent with the restoration on the Sphinx’s paws and chest.

The Dream Stela is a reused doorway lintel from Khafre’s mortuary temple. In fact, the pivot sockets on the back of the stela match sockets in the threshold of Khafre’s temple. In addition, our mapping project provided evidence that some of the masonry cladding used to restore the Sphinx came from the walls of Khafre’s pyramid causeway.

The friable native stone of the Sphinx sanctuary still erodes daily. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (previously called the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities) carried out a major restoration program in the 1980s and 1990s. They used the ARCE Sphinx Project maps to ensure that replacement masonry matched the earlier appearance of the statue.

The importance of accurately mapping ancient monuments is evident in the toll that time and the elements take on them. Today, all along the Nile Valley, the Supreme Council of Antiquities is in a race to save antiquities from pollution, rising ground water, the impact of tourism, and the natural deterioration that occurs over time. Some monuments now exist only in the maps and records made by archaeologists. What we don’t record, we lose forever.

Oldest Olive Wood in Egypt

AERA’s Multinational Research Team Discovers Oldest Olive Wood in Egypt

BOSTON, MA – Researchers at Ancient Egypt Research Associates, Inc., the premier non-profit organization conducting original archaeological research and educational programs in Egypt, have discovered new evidence suggesting that olive wood was present in ancient Egypt as early as 2551- 2523 BCE, between 500 to 700 years before previously believed, a find that may provide new insights into the life of the pyramid builders.

The discovery, made by AERA charcoal analyst Rainer Gerisch, suggests that olive wood was at least present, if not grown, in Egypt as early as the time of Pharaoh Menkaure (about 2551-2523 BCE), builder of the third Giza pyramid. Until now, the earliest known traces of olive were fruit pits found in 12th Dynasty deposits at Memphis. Even then, there are almost no other archaeological finds of olive until the 18th Dynasty (about 1569-1081 BCE).

The first definitive evidence that Egyptians were growing olives dates from the Graeco-Roman era (305 BCE-337 CE). With AERA’s new evidence, scientists can now conclude that the olive wood is genuinely part of the Old Kingdom settlement remains, dating at least 500 years earlier than any other known specimens in Egypt.

Although there is evidence suggesting that the olive wood was imported, two important facts undermine this hypothesis. It is unlikely that a highly prized and heavily pruned olive tree would ended up in the timber trade. And, since the specimens found at AERA’s excavation are mostly from twigs, the wood was probably not imported and used to carve small objects, leaving scraps as firewood that might have ended up as charcoal.

Perhaps then, the newly discovered olive wood entered Egypt with other products, possibly olive oil or more useful timber. Some archaeologists believe combed ware pottery vessels known to exist in Egypt at the time carried olive oil because they have been found in olive oil factory sites in the Levant, where people have pressed olives since the 4th Millennium BCE.

AERA ceramicist Anna Wodzinska has identified 14 combed ware sherds at the Lost City site. If the imported jars carried olive oil, prunings from the orchard might have come along with the jars as some sort of packing material or shipping crates. It is also possible that Egyptian workers brought in the olive twigs with wood shipments. When crews were dispatched to the Levant to fell trees and transport the logs back, they may also have taken firewood to use on their return voyage or to fill out extra space on their ship. Gerisch found the olive with small pieces of charcoal from other Levantine trees-cedar, pine, and deciduous and evergreen oaks-suggesting that they may have come from the Levant together.

Is it possible that Egyptians were growing olive trees? In the New Kingdom Queen Hatshepsut maintained a botanical garden of exotic plants. Perhaps Menkaure made an early and undocumented effort to cultivate olive trees in palace gardens. Few Old Kingdom town sites have been excavated extensively and sampled methodically for wood charcoal. AERA’s work may inspire others to carry out similar studies and perhaps discover more information about the role of olive trees in ancient Egypt.

AERA is a member-supported non-profit organization dedicated to high-quality original research and educational programs in Egypt. For more information about AERA or to become a member, go to www.aeraweb.org.

The discovery, made by AERA charcoal analyst Rainer Gerisch, suggests that olive wood was at least present, if not grown, in Egypt as early as the time of Pharaoh Menkaure (about 2551-2523 BCE), builder of the third Giza pyramid. Until now, the earliest known traces of olive were fruit pits found in 12th Dynasty deposits at Memphis. Even then, there are almost no other archaeological finds of olive until the 18th Dynasty (about 1569-1081 BCE).

The first definitive evidence that Egyptians were growing olives dates from the Graeco-Roman era (305 BCE-337 CE). With AERA’s new evidence, scientists can now conclude that the olive wood is genuinely part of the Old Kingdom settlement remains, dating at least 500 years earlier than any other known specimens in Egypt.

Although there is evidence suggesting that the olive wood was imported, two important facts undermine this hypothesis. It is unlikely that a highly prized and heavily pruned olive tree would ended up in the timber trade. And, since the specimens found at AERA’s excavation are mostly from twigs, the wood was probably not imported and used to carve small objects, leaving scraps as firewood that might have ended up as charcoal.

Perhaps then, the newly discovered olive wood entered Egypt with other products, possibly olive oil or more useful timber. Some archaeologists believe combed ware pottery vessels known to exist in Egypt at the time carried olive oil because they have been found in olive oil factory sites in the Levant, where people have pressed olives since the 4th Millennium BCE.

AERA ceramicist Anna Wodzinska has identified 14 combed ware sherds at the Lost City site. If the imported jars carried olive oil, prunings from the orchard might have come along with the jars as some sort of packing material or shipping crates. It is also possible that Egyptian workers brought in the olive twigs with wood shipments. When crews were dispatched to the Levant to fell trees and transport the logs back, they may also have taken firewood to use on their return voyage or to fill out extra space on their ship. Gerisch found the olive with small pieces of charcoal from other Levantine trees-cedar, pine, and deciduous and evergreen oaks-suggesting that they may have come from the Levant together.

Is it possible that Egyptians were growing olive trees? In the New Kingdom Queen Hatshepsut maintained a botanical garden of exotic plants. Perhaps Menkaure made an early and undocumented effort to cultivate olive trees in palace gardens. Few Old Kingdom town sites have been excavated extensively and sampled methodically for wood charcoal. AERA’s work may inspire others to carry out similar studies and perhaps discover more information about the role of olive trees in ancient Egypt.

Archaeological GIS at Giza

By Farrah L. Brown (GIS Specialist) and Brian V. Hunt

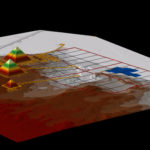

ArcScene view of the Giza Plateau.

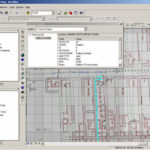

The size of AERA’s excavation at Giza’s ancient Egyptian settlement and the enormous quantity of data that it has produced could easily overwhelm. That’s why we’re employing an exciting tool—a Geographic Information System (GIS)—to aid our search to understand the processes and infrastructure that supported pyramid building at Giza.

A major goal for AERA specialists over the next few years is to publish the results of our analysis of more than fifteen years of excavation at Giza. We will offer the methodological and data-analysis of the Giza Plateau Mapping Project (GPMP) in a number of forms: in monographs, in journal articles, and on this web site. GIS will help accomplish this goal.

What is GIS?

GIS is a combination of computer hardware and software designed to store, retrieve and analyze data for which location is an important characteristic. The location information allows us to graphically map the data and view relationships to other data. Typically, we use GIS to:

- Input and store data

- Retrieve data

- Manipulate, map, and analyze data

- Create new data and reports

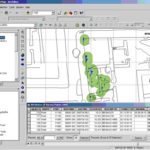

Displaying the digitized 1:100 maps in GIS.

GIS differs from the computer-aided design (CAD) and mapping tools developed during the mid-1980s. The data representation is similar, using spatial objects like points, lines, and areas, but these objects are more than just a digital representation of a paper map. GIS integrates the location and the characteristics of those objects.

GIS provides many choices not possible with conventional mapping by giving us a real-time view of an integrated data source that includes spatial objects, tables, imagery, photographs, as well as links to documents and other related information.

The potential for spatial analysis at Giza

We are involved with a remarkable archaeological project, with data that has much potential for spatial analysis. We are also faced with a huge challenge.

Before we can expect results from the many possible analyses offered by GIS technology, we must address three key elements for each archaeological feature, artifact, or component of architecture to be represented in the GIS: spatial location, attribute data, and relationships to other objects.

Spatial location and attribute data

Displaying attribute data of a selected object in ArcMap.

Every object in a GIS must be correctly located in space using precise geographical coordinates, and its nature accurately described by way of attribute data.

Geographic coordinates for each feature are recorded during excavation using survey equipment and discernible locations on the excavation survey grid. Attributes, in our case, are data describing the excavated and unexcavated archaeological materials.

Archaeologists depict attributes in drawings and document them on the various excavation forms. The data that the various specialists create during analyses is also a type of attribute that we will link to spatial objects in the GPMP GIS.

Topology

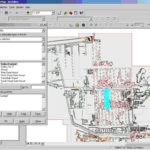

Displaying the GPMP Features dataset and typology in ArcCatalog.

Context is everything in archaeology. The spatial relationships of an archaeological feature, artifact, or architectural component to its surroundings are essential to our research.

In a GIS, management of these relationships is possible due to “topology,” or rules of behavior, which can be established and validated using tools in ESRI’s ArcGIS software. These rules impose restrictions on the placement of objects within the GIS and govern such spatial characteristics as overlap, containment, contiguity, and exclusion.

It’s these properties of attribute data and topology, which describe an object’s characteristics and spatial relationships, that set geographical data apart from other types of information stored in databases.

Asking questions

Ultimately we want to answer questions with our data using GIS.

- What is it?

- Where is it?

- What is its relation to other objects?

Selecting all lines labeled Gallery Example from a digitized layer.

What is it?

Object-type questions are answered in a GIS by selecting objects based on specific attributes. These operations can include one or more objects and objects with more than one attribute.

For example, in our analysis of the Giza data, we might be interested in identifying the locations of all mud brick walls or all Late Period burials. We could easily select and view these locations if, in the attribute table, the digitized walls are described by type and the burials described by time period.

Where is it?

When we analyze the locations of objects, we can use operations involving Euclidean distances (the “ordinary” distance between the two points that one would measure with a ruler) or descriptions of location. We can create buffers to select objects within a certain distance of other objects with specific characteristics.

For example, at Giza, we might be interested in Late Period burials but only those that are within 30 meters of a mud brick wall. Again, this would be a simple operation in the GPMP GIS. Using a tool in ArcGIS, we could create a 30 meter buffer around all walls labeled “mud brick,” within which all burials labeled “Late Period” would be selected.

What is its relation to other objects?

In a GIS, we use topology to answer questions about the relationships between objects. We can establish rules to govern object placement in the GIS with statements such as: “objects of type A must be contained within objects of type B.”

Analysis based on topology becomes especially important when two archaeological features share a common boundary. It is important, in this case, to eliminate any gaps between the two spatial objects so that analyses will return correct results.

In our case, we might be interested in mud brick walls that are abutted by a certain type of soil, the soil types that surround the Wall of the Crow, or sealings that are contained within certain types of features.

We can combine any or all of these three types of spatial analyses involving object type, location, or relationship for a more complex analysis. For example, we might be interested in the locations of Late Period burials that are within 30 meters of mud brick walls that are 2 meters or taller that are abutted by dark, compact soils that contain sealings with markings related to the period of Menkaure.

What can GIS do for archaeologists?

The capabilities of GIS will provide great benefits for analysis and management of the important archaeological and World Heritage site at Giza. The tools available with ArcGIS will enable archaeologists at Giza to:

- Organize existing data, promote data consistency, and facilitate accurate data entry and data collection.

- Integrate different data formats into one central data store.

- Provide easy access to data sources and user-friendly mapping tools for team members.

- Visualize the archaeology and modern landscape of the Giza Plateau in 2D and 3D.

- Explore distributions and densities of specific artifact, feature, and architectural types.

- Analyze artifact groups and their relationships to possible activity.

- Document and manage environmental impacts and modern-day threats to the site.

The Archaeological community

Sharing ideas about problems and issues that are specific to archaeological GIS is a key to the success of the GPMP GIS and to the contribution of best practices for GIS in archaeology.

We had the privilege of hosting ESRI developer, Tim Hodson, for a tour of the Giza site, where we also had a chance to discuss several data issues with him.

We also attended ESRI’s July 2005 International Users Conference in San Diego, California where we had the opportunity to attend technical workshops, presentations, and the Archaeology and Historic Preservation Special Interest Group Meeting.

The GPMP GIS team will continue to build relationships with other GIS professionals, exchange information on similar datasets and problems, and contribute to the design of a flexible data model that is suitable for use on a wide variety of archaeological excavations.

Conclusion

GIS is a powerful tool that will open doors to an entirely new aspect of analysis for archaeological exploration at Giza. GIS will allow us to implement a data model that is specific to our data management and analysis needs.

We’ve already made considerable progress in the initial months of GIS development. Our efforts to understand the GPMP dataset and to construct a digital base map for the excavation have been a success.

We are currently working diligently to explore the extensive archive of excavation data, organize and check thousands of drawings, integrate multiple specialist databases, and link the GIS to an existing online excavation database.

We’re also in the process of designing and constructing a series of geo-databases in the GIS to house and enable analysis of all of the data collected at Giza.

Our involvement in the larger GIS community will be a catalyst to our efforts, and we hope that our contribution of methods and data-analysis results will be a positive influence on the use of GIS in archaeological investigations.

Pyramids and Protein

By Dr. Richard Redding (Archaeozoologist, University of Michigan) and Brian V. Hunt

Egyptians of the 4th Dynasty (2575-2465 BC) witnessed the construction of some of the world’s most enduring symbols: the pyramids, the temples, and the Sphinx of Giza. Tens of thousands of workers came together in great public works projects, undertaken to ensure the successful afterlife of kings. The problems this created for planners and administrators were monumental as well.

They could not, for example, solve the problems of provisioning a city of ten or twenty thousand by just scaling up the methods used for a village of a few hundred. The methods the Egyptians employed at Giza may have influenced the royal administration of the country for millennia to come.

How did the royal house manage to feed this massive workforce? What can the remains of animals in the archaeological record at Giza tell us about how the Egyptians solved this problem?

Prime beef for pyramid builders

In an area of the world where people have traditionally reserved meat eating mostly for special occasions and feast-days, we have found evidence that the ancient state provisioned the pyramid city with enough cattle, sheep, and goat to feed thousands of people prime cuts of meat for more than a generation—even if they ate it every day.

We have examined and identified over 175,000 bones and bone fragments from the excavations at the Giza pyramid settlement. The bones are from fish, reptiles, birds and mammals. About 10% have been identifiable to at least the level of the genus (a group of closely related species).

Cattle and sheep dominate the fauna. We have found:

- 3,356 cattle fragments

- 6,897 sheep and goat fragments

- 536 pig fragments

The ratio of individual sheep and goat to individual cattle is 5 to 1.

It might appear that sheep and goats were more common at Giza than cattle, and that sheep and goats were more important. But remember that an 18-month-old bull produces 10 to 12 times as much meat as an 18-month-old ram

The ratio of sheep to goats at Giza is biased towards sheep. For the entire settlement site, the ratio of sheep to goat is 3 to 1.

There is a low frequency of pig bones.

The cattle and sheep consumed at the settlement were young.

- 30% of the cattle died before 8 months, 50% before 16 months, and only 20% were older than 24 months.

- 90% of the sheep and goats survived 10 months, only 50% were older than 16 months, and only 10% older than 24 months.

The cattle and sheep are predominately male.

- The ratio of male to female cattle is 6 to 1.

- The ratio of male to female sheep and goats is 11 to 1.

What does this tell us about life at the pyramid settlement?

Problems in scale

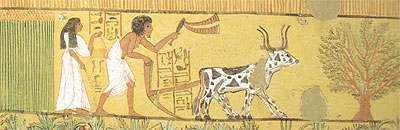

The agrarian society of ancient Egypt was centered on crops and animals. The Egyptians’ colorful tomb paintings depict a rich agricultural life and we find evidence of this life in the archaeological remains of their settlements.

Agricultural scene, tomb of Sennedjem at Luxor.

The Egyptians could not catch fish, birds, and wild mammals in numbers adequate to support a large settlement like that at Giza.

Feeding the pyramid builders required an increased production of domestic mammals: sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. But there may have been inadequate space near Giza to support large herds of animals to feed the pyramid builders. Where did the supply of meat protein come from?

Expectations at Giza

Our models of animal use in the Middle East and Egypt are based on studies of the ecological, reproductive, productive, physiological and behavioral characteristics of domestic cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. These models help us make predictions.

The royal administrators had to develop a system that encouraged the production of animals beyond the needs of the villages of the Nile Delta and the Nile valley. They then collected the surplus and moved it along the Nile to Giza.

If the Giza settlement was organized and provisioned by a central authority (the royal administration), then we expect certain evidence to emerge from the archaeological data. Based on our knowledge of agrarian societies and food production, the evidence at Giza should show:

- Pigs are evident at very low frequency.

- Cattle and sheep dominate the fauna.

- The cattle and sheep are mostly young males.

Animal utility

Pigs would have been unsatisfactory for provisioning a workforce on a large-scale in the ancient world. They cannot be herded and do not travel well over long distances. There are no nomadic pig herders anywhere in the world today.

Pigs have a dispersed birthing pattern that is not seasonal; they give birth up to three times a year. Therefore, young pigs are available at almost anytime for consumption.

Pigs provided no secondary products (hair, milk, etc.) and were therefore less valuable than cattle, sheep, and goats.

Because of the pig’s unsuitability for feeding workers on a large scale, the Egyptian workforce administrators were not interested in them as stock, and pigs were not involved in inter-regional exchange the way other animal stocks like cattle, sheep, and goats were.

Our studies indicate, however, that while the central authority did not consider pigs a valued provisioning resource, Egyptian families reared pigs for protein. Even today, in rural and urban areas around the world, farmers and non-farmers use pigs (where they are not proscribed by religion).

Delivered when needed

We know that the Egyptians recorded regular and detailed counts of animal stocks throughout the Nile Valley. These counts are a clear indication of the value of animals as a commodity to the state.

Although they cannot provide the quantity of meat that cattle do, sheep and goats are valuable for similar reasons. They can be herded and provide secondary products.

Sheep, goats, and cattle can and do travel long distances. Americans in the 19th century drove cattle to market over vast distances. Nomadic sheep and goat pastoralists today move animals 1,000 miles (1,609 km) by hoof in migration (e.g. Qashghi in Iran).

In the 4th Dynasty, it was not possible to rear sheep, goats, and cattle around Giza in the numbers needed for the pyramid builders. We are working on an estimate of the farm area required to rear these animals in sufficient numbers to provide a surplus that would support 8,000-10,000 workers laboring at ancient Giza. Preliminary estimates suggest a required area substantially larger than the Giza environs would allow.

The administrators would have organized drives of sheep, goats, and cattle between the Nile Valley and the high desert to move the required animals to Giza. In a foreshadowing of modern manufacturing, the animals would arrive in waves—a “just in time” delivery system.

Secondary produce

Sheep, cattle, and goats all have secondary products beyond their meat:

- Sheep’s wool can be woven for cloth.

- Leather is valuable for clothing and tools.

- Cattle bones can be used to make tools.

The ancient inhabitants may also have consumed milk from cows and goats, but not in such large quantities that it would have been signficant for the diet of the pyramid labor force. Secondary produce makes all of these animals more valuable resources.

Birth cycles and surplus males

Sheep and goats have tight birthing seasons (compared to pigs) and produce age classes from which the young male surplus needs to be harvested. As with cattle, female sheep and goats are needed to produce offspring, while only a few males are needed for breeding.

Without a central authority, this surplus creates a labor problem for herders and agriculturists. Do they reduce the herd size or increase meat consumption seasonally? It would therefore have been relatively easy for administrators to encourage villages to increase production. The central authority then becomes a convenient market for the surplus in exchange for goods and services.

Ideal grazing

In Egypt, ranchers would have raised cattle in grassy areas with wells and watering holes like the Nile Delta. They would have raised sheep in the drier areas. Goats could have thrived in both places and would have complimented cattle rearing because these animals do not compete for food.

Imagine a division across the Nile Delta or Valley: cattle and goats in the middle and sheep and goats along the edges. Sheep and goats would go out into the high deserts in the rainy season and returned to the edges of the delta or valley in the dry season.

Kom el-Hisn: contradiction and example

The Old Kingdom (5th and 6th Dynasty, 2465-2150 BC) Egyptian village, Kom el-Hisn, was excavated by archaeologists in 1985, 1986, and 1988. A contradiction appears in the archaeological record there.

There is abundant evidence of cattle dung from the Old Kingdom level at Kom el-Hisn, which means there must have been large herds there. Yet the cattle bones indicate two things: the numbers of cattle slaughtered at Kom el-Hisn are relatively few and the bones that exist are from very old or very young individuals.

Where are the prime, young males, which provide the best cuts of beef?

The residents were not consuming the cattle they reared and were consuming few of the sheep. They only used very old animals or animals that were very young and ill. The residents of Kom el-Hisn were dependent on the pig as a source of protein and, unsurprisingly, we find a dominance of pig bone at the site.

Kom el-Hisn is just 4 kilometers from the ecotone where the Nile Valley meets the desert. The Egyptians could have reared cattle in the grassy areas around their villages and sent herders out with flocks of sheep and goats to exploit the ecotonal area.

The royal cattlemen periodically gathered up herds of young, male cattle and sheep (1 to 2 years) and drove them along the Nile to a central point for redistribution. These young male animals were not consumed locally and so their remains did not enter the archaeological record at Kom el-Hisn.

Cattle were raised at Kom el-Hisn but not consumed there. Where were the consumers?

We hypothesize that Kom el-Hisn was a regional or provincial center for raising cattle, but that the young males were sent to the core area of the Old Kingdom state—the capital zone and the pyramid zone—for feeding cities. Our systematic excavations and retrieval of animal bone from such core-area settlements, like Giza, allow us to test our hypothesis. In fact, we find the inverse ratios of Kom el-Hisn: lots of cattle, sheep, and goat but very little pig.

Conclusions

Our study of the 4,500-year-old animal bones at Giza are another piece of the puzzle of life in ancient Egypt. Based on the data above, we see that the pyramid settlement at Giza was a well-provisioned site, supplied by the central authority; the archaeological pattern is not one of a livestock producing site.

A central authority gathered predominately young, male sheep, goats, and cattle and brought them to the site to feed the occupants; the bones of these animals dominate the faunal remains and pigs are in very little evidence. Once again we find that an interdisciplinary approach to our examination of the evidence at Giza, yields a much fuller picture of life at the settlement and reveals clues to the organization of the ancient Egyptian state.

More to tell

There’s yet another story to tell about animal use at Giza. Further analysis now indicates that species are not equally, or randomly, distributed around the site. Patterns exist in animal use across the site and these patterns need to be explained.

Please visit our site again to read a future article that discusses the unequal distribution of animal remains across the pyramid settlement and what that might mean about the people who lived there.

A Pyramid-builder’s House

By Edward Johnson (Archaeological Conservator), Günter Heindl (Architect/archaeologist), Ashraf Abdel Aziz (Archaeologist), and Brian V. Hunt

ETH before reconstruction

Trying to visualize living space from an architectural plan can be challenging. Walking around in a 3-dimensional space provides a different perspective on the use of that space.

Over a period of more than ten years, AERA archaeologists have exposed and analyzed a number of architecturally varied structures at the Giza pyramid settlement. In the autumn of 2005, AERA initiated a project to not only conserve but to reconstruct one architectural unit of the ancient Egyptian settlement we are excavating.

Of three candidate test structures, which varied in form and content, we selected the building with the smallest surface area and volume. The structure sits among other ancient Egyptian housing at the eastern reach of our concession, an area we appropriately call Eastern Town.

Our test object, Eastern Town House (ETH), is an almost completely intact house foundation with clear evidence of remodeling during the period in which it was inhabited, during Egypt’s 4th Dynasty (ca. 2575-2465 BC).

Dan Housel and Emma Hancox excavated ETH in 2004 and recorded six phases of ancient remodeling. The layout of the house, the objects found, and attested to activities of a family household, like houses at the Middle Kingdom pyramid-town at Lahun.

ETH included an enclosure wall, courtyards, a vestibule separating public and private areas, a main room with a sitting bench, and a sleeping niche.

There was an area for grinding and storage facilities, pottery jars set in the floor, and a small circular granary. The second set of courtyards could be entered both from the front and the back of the house. Here we found traces of baking and cooking.

The spaces inside ETH would have been crowded and bustling, with no provision for the kind of individual personal space taken for granted by many cultures today.

Conservation challenges

There is little in the Egyptological publications about mud brick conservation, although a number of archaeological missions have carried out extensive conservation projects. Our colleagues from other missions gave us valuable input as we surveyed existing mud brick conservation near Giza, Abu Sir, Dahshur and Abu Roash.

Every conservation project is unique, due to the local environmental exposure and the construction materials used in building. The ancient inhabitants built Eastern Town House of mud brick, with a few elements of undressed stone and possibly wooden columns. Ancient mud brick presents great challenges to conservation due to its fragility.

Options

We needed to use a conservation technique that was best suited to the environment and structures at Giza.

Enclosing ETH in a protective structure was less than ideal for aesthetic and practical reasons. Such an enclosure would also have limited effectiveness. Capping the ancient walls with a new layer of mud brick was inadequate because it might actually accelerate the deterioration. The original walls would still be exposed to rain—water being mud brick’s greatest enemy. Chemical consolidants arry their own problems and limitations, penetrating only the surface of a wall, creating stress with the raw core.

Backfilling ETH and burying the structure would effectively protect the ancient mud bricks and provide a base for reconstruction.

Backfilling and reburying

The reason these ancient walls survive to our time is because they were buried and protected beneath the sand. We chose to rebury Eastern Town House to recreate its pre-excavation environment.

To isolate our reconstruction from ground moisture, we backfilled the walls beneath a deep layer of clean sand upon which we constructed a platform of mud brick. The raised, mud brick platform provided a base for the reconstructed house.

As we built a framing wall around ETH, workers backfilled directly over the ancient structure, allowing us to reconstruct ETH at the same site and with the same orientation as the original.

The platform

The platform had to be strong and stable to support the reconstructed house. We examined several options for building the platform, including single- and double-layered solutions.

The single-layered options may have been adequate, but caution led us to carefully consider the pressure the walls would be subject to with being walked upon or bearing the weight of the reconstructed walls.

We chose to lay a double-layered mud brick platform directly on the sand. We bonded the bricks with sand and mortar, and covered with a plaster made with Nile clay, chaff, and water.

We constructed the lower layer with stretchers, headers, and half-bricks arranged relatively irregularly (long, continuous joints decrease stability). We laid The second layer in a herringbone pattern. We now had a solid base on which to construct new walls.

Material

Proper techniques require that everything we do in conservation and reconstruction must be reversible (which is a problem with chemical consolidants). Future archaeologists and researchers must be able to undo what we have done so that they can study the original structure underneath.

Best bricks

AERA archaeologist, Ashraf Abdel Aziz, is creating a typology of ancient mud bricks. It is interesting to note that he has identified differences in bricks from buildings across the Giza Plateau. Ashraf brought his knowledge to our reconstruction project and was involved in our analysis of other conservation sites in Egypt.

We wanted to use brick of similar material and of the same approximate size as the brick originally used in the construction of the Eastern Townhouse (28 x 14 x 8 centimeters). We estimated that the platform base, framing wall, and house walls of ETH would require approximately 24,500 bricks.

Salah, our longtime guard at the site, of somewhat advanced age, had agitated from the beginning for an opportunity to make bricks. When he persisted, we acquiesced in order to raise the production rate.

To our delight, he made the best bricks of all, using a somewhat different technique from all the other brick makers. He put the mixture in the brick-forms without re-watering, the wet mortar, packed it down forcefully by hand, and added a little water on the top surface to smooth it down.

He made a very well-formed brick (without any temper other than sand) with clean sharp edges, completely filled ends, and without any melting or slumping from excess water.

He was a bit slower than the younger brick makers, but his product was so superior, that we continued to rely on him in this capacity until we finished.

The walls

We used varying heights of walls to demarcate different parts of the house complex. The completed reconstruction has:

- four courses of bricks for features like the silo

- six courses for the courtyard walls

- eight courses for the central building—the core house

There are enough substantial walls left in the settlement to allow us a clear understanding of the ancient construction techniques. We built our new walls in exactly the same way that the old walls were built.

We filled the wide joints with brick chippings and mortar. The corner bricks of each layer were measured and adjusted to the same height using an automatic level.

As the brick layers rose we incorporated doorways. We built a limestone threshold for the main entrance in the west wall based on examples we have excavated at the site. For the entrance of the private quarters, we installed an exact copy of a stone door socket that we excavated in situ.

The floor

To level the floor, we used a layer of coarse plaster followed by a finer plaster made of sieved Nile clay, sieved sand, straw, and water. We left the plaster to dry for a few days with a watchman on duty each night to protect the floor from damage by feral dogs.

Reconstructed features

Finally we added the grain silo, the bed, two wall extensions, and what may have been a grinding vat.

The ancient grain silo was originally constructed as an ellipsoid, because a full circle would have left too little room for people to squeeze between the silo and the adjacent walls. We reconstructed the silo to reflect this interesting example of how the occupants adapted the structures of everyday life to the tight spaces in the house.

Based on comparative evidence, we estimate ETH could have housed four to eight people (perhaps more). The house had only one bed platform, which raises the question of how many people actually lived, slept or otherwise utilized the house.

Conclusions

We may surmise, based on what we know about ancient Egyptian society and households that Eastern Town House was a crowded place by the standards of housing in modern, developed societies but perhaps typical for ancient Egypt. Our reconstruction revealed a little urban estate that felt much more roomy than the footprint we mapped during excavation.

Within the confines of the house and courtyards, the cooking and craft work in and around ETH would have made for an often smoky place. Inhabitants would have constantly negotiated space with other people, stored goods, and animals, including sheep, goats, and possibly a pig or two.

While the original structure is now unavailable for viewing, Eastern Town House is now protected from the elements. The reconstruction represents an extremely faithful model of what this structure really looked like and how it functioned. Our techniques are entirely reversible and future researchers can undo what we have done.

Reconstructing Eastern Town House and building other test walls on the Giza settlement site help us understand the living spaces and construction methodology employed by the ancient pyramid builders. The test walls allow us to monitor erosion—caused by wind, rain, and rising moisture—before proceeding with further conservation.

We look forward to doing more of this kind of work at the city of the pyramid builders. Incorporating interdisciplinary, experimental archaeology into our mission broadens our interpretation of the reality of the ancient Egyptians and reinforces our methodology.

Flint Industries at Ancient Giza

By Tim Stevens, Lithics Analyst, and Brian V. Hunt

Flint blade from Giza

Many people think of stone tools as strictly Stone Age technology. The fact that people used chert and other stone for tools is what defines prehistory as the Stone Age. This has led to an under-appreciation of the role of stone tools in sophisticated, literate societies, such as that of Old Kingdom Egypt (2575-2134 BC).

To date, our specialists have examined over 33,500 flint artifacts (flint and chert are geologically distinct but “flint” is often used to refer to objects made from chert) from the Lost City of the Pyramids. Chert can be shaped into very effective tools and its presence in huge quantities on the desert surface made it a natural resource for the pyramid builders.

The Bronze-Age Egyptians’ introduction of metals and other materials certainly changed the relative importance of chert, but it continued to be used during the Old Kingdom and later. Chert is perhaps so common that archaeologists sometimes ignore this simple material in favor of artifacts like pots, which are familiar because we still use pottery, and inscribed sealings because hieroglyphic texts speak more directly than material like chert.

GPMP specialists consider all material valuable to our analysis. The occupants of the Lost City not only used chert in a wide variety of situations, domestic and industrial, but it was also a raw material integral to economic networks extending far beyond the Giza site.

Composition and use

Tomb scene: butchering with a flint knife

Chert is a very fine crystalline material often found in limestone. Geologists think that at Giza it formed as deposits on the desert surface from dissolved limestone or from another as yet unidentified source.

Chert differs from other materials formed of silicon dioxide (silicas such as glass, quartz, opal, and agate). Its crystal structure is so fine that it allows the chert to be flaked into pieces which are not only strong, but retain razor-sharp cutting edges. This differs from quartz, in which large crystals allow only crude edges to be formed.

Two stories

There are two kinds of chert at Giza and each has its own implications for social and economic activity.

- Locally abundant, poorer-quality raw material (knapped by Giza inhabitants for immediate use and then discarded).

- Imported, good quality raw material (acquired and distributed in the form of refined tools requiring preservation and maintenance).

Local Industry

Chert cores from Giza

The first industry is numerically more significant. The most common type of chert artifact at Giza is the simple flake, which ancient toolmakers removed from a larger core using a hammer stone.

It takes no more than a few seconds to produce a viable cutting edge from a chert pebble once some basic skills are acquired. These flakes are used for cutting, scraping, trimming, etc., and their usefulness is not inhibited by the crudeness of their manufacture.

Many of the pieces we’ve excavated appear to have been used; the edges show small flake removals known as “edge damage.” Other pieces have evidence of retouching to strengthen or re-shape the edge and are classed “flake tools.”

The examples of this group are made of local chert, found as pebbles in or on the desert surface or possibly quarried in small amounts from the great quarries on the Giza plateau.

This material is not of particularly good quality because it is naturally quite coarse and does not flake well. Or, as a result of desert weathering, it is liable to split unpredictably when struck. This combination of features seems to have dictated the types of artifacts that the inhabitants produced from local chert.

Imported industry

The second flint industry at Giza was comprised of good quality chert from sources outside of Giza or sources that have not yet been identified at Giza.

These types of chert occur naturally at Giza but in negligible quantities. But we do not find cores of these materials at the site, which further suggests that the settlement inhabitants imported tools and partially finished cores, possibly from sites like Abu Roash, just north of Giza.

This imported chert was used to produce:

- Bifaces (flaked on both faces)

- Triangular scrapers (usually dark chert)

- Blades and blade tools (usually pale pinkish-brown or light grey)

Rough tool from the Giza settlement

The production of blades, blade tools, and bifaces are difficult tasks, even for modern knappers. Ancient producers would have been skilled artisans with a good knowledge of the raw material and the technology required to produce the artifact types we find as exotic (imported) material at Giza.

The strong edges produced from these materials were more suitable for repeated scraping of things like animal hides. They were also more amenable for use in composite tools, such as a sickle or knife, because they did not snap as easily as the inferior chert did when used.

Whilst the imported chert is less significant quantitatively, its presence suggests three things:

- There were economic networks in which chert was an important commodity.

- There were specialists in chert mining and manufacture working at sites economically connected to Giza.

- Similar, or even perhaps the same, technicians operated at Giza itself.

Implications

It seems reasonable to suggest that chert blades may have been imported in bundles as raw material, and the bifaces as partially worked blanks. The absence of cores of exotic chert suggests that the tools were imported, but we do not yet know whether they were transported as raw material or finished tools.

We find distinctive flakes from the retouching of blade tools and scrapers and the thinning of bifaces distributed across the settlement site in varying quantities. They were formed from the initial refinement of raw material or from the inhabitants’ maintenance of used pieces.

One area where flakes from good tools were common is the courtyard of the Royal Administration Building (RAB). The ancient Giza workers may have refined or maintained some tools for distribution from the RAB, a structure possibly associated with a centralized distribution system of the royal house (as indicated by other artifacts). It is conceivable that someone controlled access to good quality tools in that these were not as disposable as tools made from local chert.

Sharpening a flint knife

We also find good quality blade tools, bifacial knives, and waste flakes in another area in relatively large quantities, where sealings are also abundant. It is possible that the control over good tools extended to their distribution only to workers of higher status or skill. It is worth noting that almost no chert of the good, imported type occur north of the Wall of the Crow, where a scrappy local chert assemblage predominates.

Conclusions

The presence of a vibrant flint industry at Old Kingdom Giza again shows that even in a sophisticated age of metal and writing, the ancient Egyptians made use of all available technologies to achieve domestic and industrial ends. The greater abundance of imported chert in the Royal Administration Building and the Western Town areas of the pyramid settlement reinforces the emerging picture of higher-status occupants in these areas.

A Girl and Her Goddess

By Marie-Astrid Calmettes (Egyptologist), Jessica Kaiser (Osteologist), and Brian V. Hunt

Hatmehyt amulet

More than 2,500 years ago, a very ill young woman died and was buried at the already long-abandoned site of the city of the pyramid builders at Giza. Her grave goods included an amulet of an obscure goddess that suggests the woman may not have been from the Giza area.

Not only that, but she may not have been of Egyptian descent.

AERA’s primary investigation at Giza is the 4th dynasty settlement of the pyramid builders. In one quarter of our dig site, however, we’re faced with the reality that hundreds of Late Period (747-525 BC) burials and a few Old Kingdom (2575-2134 BC) burials cover the site above the 4th dynasty levels. We cannot investigate the older levels without first carefully excavating, recording, and removing the Late Period burials.

At the end of the 4th Dynasty, the pyramid builders abandoned their city to the desert sands. Two millennia later, the ancient Egyptians began burying their dead at the site of the former Giza workmen’s village, by then deeply buried under sand. The first of these burials were interred on a slope along the western edge of our dig site.

A sick girl

Note the Hatmehyt amulet near the woman’s shoulder.

In 2005, osteo-archaeologists Jessica Kaiser and Tom Westlin uncovered 11 burials in this area of the Late Period cemetery. Recovered ceramics suggest the burials date to the 25th Dynasty, earlier than other Late Period burials at our site.

One of the richest interments of this group, burial 407, was that of a young woman of about 16 to 20 years old. Analysis by AERA osteologists showed that she suffered health problems during her short life. Lines in her tooth enamel (enamel hypoplasia) suggest that she was seriously ill during tooth formation in childhood. She survived this illness, but severe pitting in the roofs of her eye sockets (Cribra orbitalia) indicate she probably suffered from iron-deficiency anemia at the time of her death.

Finally, marks on the bones around the ear canals of this young woman (mastoiditis) point to a severe ear infection. This may have been what killed her, since deaths due to ear-infection complications were not uncommon before the introduction of antibiotics.

A non-Egyptian burial?

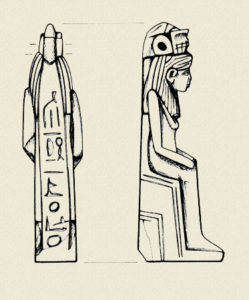

Drawing of Hatmehyt amulet

Although this is clearly an Egyptian interment with Egyptian burial goods, our craniometrical analysis of the woman implies that she may have been of Central European descent rather than Egyptian. If the amulet suggests the girl had a connection with the Delta city of Mendes (more below), that may be the link with Central Europe, as the Delta had immigrant colonies in the Late Period.

Because of the poor preservation of many of the Late Period skeletons, only a few skulls allowed craniometric analysis. The range of natural variation in the skeletal population is therefore unknown. However, our analysis is based on the vast database in FORDISC 2.0, which also includes both Egyptian (Saite) and Sub-Saharan crania, and burial 407 did not match either of those groups.

Hatmehyt: a sacred connection to Mendes

The woman in burial 407 was interred with a collar made of beads and a faience amulet, about 13 cm high, to protect her in the afterlife. Initially we thought the amulet represented Isis, a very powerful and important mother-goddess of late Egyptian history.

Although the hieroglyphs carved into the amulet are difficult to read and cannot be used to identify the goddess, she wears a headdress topped by a fish. The fish is a key indicator of Hatmehyt, a goddess known as “Foremost of the Fishes.”

Hatmehyt was a local deity, native to Mendes, a town in the eastern Delta. The goddess is often shown seated on a throne with a fish headdress and occasionally crisscrossed with incised lines, perhaps to indicate water. On our amulet, the tail of the fish was long, going down the back of the goddess’ head and then curling back up to create a loop for attaching the amulet to the necklace.

Occasionally Hatmehyt is depicted solely as a fish, like the amulets in the British Museum described by Egyptologist W.M. Flinders Petrie. But her identity is more secure when she takes the form of a woman with a fish headdress, as is the case with our specimen.

Why Hatmehyt?

Amulet with beads from burial necklace

Very little is known about Hatmehyt. She seems to have been a minor goddess, important in Mendes but perhaps not beyond it. Her earliest documented appearance is in the 21st Dynasty, but she may date from earlier periods.

Her epithet “Foremost of the Fishes” is known from the Old Kingdom in the geographical processions with rows of nome deities offering the products of their nome to the gods. But the name “Hatmehyt” is not known before the Ramesside period.

Dr. Richard Redding, our faunal analyst, identified the fish on our amulet as a Schilbe (probably Schilbe mystus, the more northerly of that Nile species), the sacred fish of Mendes.

Hatmehyt may have been selected for inclusion in this burial for a couple of reasons. The Schilbe was said to be in front of other fish; that is, it goes faster and may jump over the water surface. The dead would have to cross the waters of the underworld on their journey to the afterlife and the amulet would offer protection.

In some texts, a fish helped search for parts of Osiris’ body after he was dismembered in the myth of Osiris and Seth. Osiris, of course, was an important deity whom the deceased would meet at the conclusion of her journey through the underworld.

Conclusion

The sacred and profane history of the site of the ancient Giza settlement is richly varied. Although abandoned after the construction of the pyramids, the site apparently retained some sacred association, as the site was not reused until the Late Period Egyptians established their cemetery there. The Late Period burials are teaching us more about the burial practices of that time and adding an important chapter to the history of the site. Once in a while, we are rewarded with something special, like the poignant grave of an ill young woman, protected by a goddess obscure to us but important to her.