The ancient bedja.

How did the ancient Egyptians feed thousands of workers at Giza? We know from ancient texts that a staple diet of bread and beer were disbursed as rations in royal labor projects. What kind of bread did the pyramid builders eat? In September and October 1993, The National Geographic Society funded our experimental archaeology project to help answer this question.

Pyramid builders’ diet

Hieroglyphic texts tell us that Old Kingdom food production and storage facilities fell under an institution called per shena (written with the house and plow signs, roughly translated to “house of the commissariat”). This term indicates a food production establishment that included bakeries, breweries, and granaries. Evidence discovered from Elephantine Island in southern Egypt all the way to Palestine indicates that bread baking in bedja was a common and wide-spread practice for nearly 500 years.

Large, crude ceramic bedja bread molds.

In AERA’s 1991 season we found two bakeries, at that time the oldest known bakeries from ancient Egypt. These bakeries are the archaeological counterparts of the bakeries depicted in many scenes and limestone models from Old Kingdom (2575-2134 BC) tombs.

Fragments of the large, bell-shaped bread pots like those we see in the tomb scenes litter the Lost City in the hundreds of thousands. Labeled bedja in the tomb scenes, the largest weigh up to 12 kilograms each (26.5 pounds). We have found many intact examples at our site as well.

Two Giza bakeries (1991-92)

Mixing vats

At Elephantine Island our German colleagues excavated a bakery in which the bakers allowed the ash to accumulate nearly to the roof. The accumulated ash preserved the columns, about 28 cm (11 inches) in diameter, to their total height of 3.20 meters (10.5 feet).

Hearths and depressions

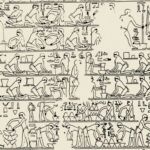

Tomb scene of bread-baking

In our bakeries, two rows of depressions (looking like oversized egg cartons) had been dug into the floor to serve as receptacles for the preheated bedja. Tomb scenes show a secondary bedja placed upside-down as a cover over the filled bread mold. We think the covers were pots that had been preheated on the open hearth. Hot ashes were probably piled around the two pots to complete the baking process, as suggested by the abundant ash and charcoal fill of the depressions.

Bakery attachment

Archaeologists have found that ancient Egyptian food production facilities are generally attached to some kind of household—the household of the king (a palace), the household of a god (a temple), the household of a governor (a manor), or the household of a private person.

The bakeries in A7

The bakeries we found at our site, on the other hand, appear to belong to industrial-scale production. But instead of building for an economy of scale (building one large industrial-capacity bakery) the Egyptians built many household-sized bakeries near each other. This fits in many ways with the kind of social structure that permeated all of ancient Egypt. Most production was done on a household level: cooking, pottery making, agriculture, metal working, and textile manufacturing, etc.

Ancient Egyptian households typically had a variety of specialized work spaces attached to them: granaries, bakeries, butcheries, weaving, carpentry shops, etc. The inhabitants of this pyramid city seem to have reached for large-scale production by enlarging bread molds and replicating household production facilities many times over. These bakeries were certainly part of a large, specialized production center—a state institution of the royal house.

We have here the clearest physical example of the kind of state (or estate) bakery labeled as per shena, like that in the tomb scenes of the 5th Dynasty official, Ty, at Saqqara. We found a possible corrupt writing of per shena etched crudely on a sherd (pottery fragment).

Use

It is interesting to note that apparently, as the inhabitants used the bakeries, they allowed them to simply to fill up with ash. By the final days of the bakery, the ash filled each room to the brim of the vats.

At Elephantine Island our German colleagues excavated a bakery in which the bakers allowed the ash to accumulate nearly to the roof. The accumulated ash preserved the slender, wooden columns, about 28 cm (11 inches) in diameter, to their total height of 3.20 meters (10.5 feet).

Fuel

Egypt is a desert country that does not have large forests to provide wood for fuel. Although wood was an expensive resource, the Old Kingdom Egyptians seemed to have burned it with abandon at Giza for a variety of purposes. Cooking and baking bread on the scale that the Egyptians were doing at the Lost City would have required a constant supply of fuel. The fuel was mostly acacia, which grew naturally across a wider area of Egypt along the low desert.

Stack heating replica bedja over a fire.

Some of the acacia may have been prepared as charcoal before being transported to Giza, as charcoal is much lighter than wood and therefore easier to transport. Even if this was the case, the builders of the pyramids were also burning wood to make gypsum to use as mortar for construction and to make and harden copper tools. We extracted small samples of gypsum out of the Giza Pyramids themselves in order to do radiocarbon dating in 1984 and 1995.

The ancient builders were probably also consuming vast amounts of acacia, which produces a hot fire, for the preparation of copper tools. Indeed, they may have amassed the largest concentration of copper tools anywhere in the world during the third millennium BC because of all the tools need to build the giant pyramids.

In a settlement the size of the Lost City, there must have been an almost permanent haze of cooking smoke across the low desert below the pyramids. Altogether we can say that between cooking, making mortar, and working metal, the Lost City was a thermodynamically expensive site: the inhabitants burned a lot of resources to produce food and material for pyramid construction.

Experimental archaeology

Recreating the ancient bakery.

The bakeries we found at Giza raised some specific questions:

- Why were the bedja stack-heated prior to baking?

- Did the bedja act like miniature ovens?

- Was ash raked around the preheated pots?

- What kind of bread was ultimately produced?

Experimental technique

Baking in progress.

We discovered that the low walls of the ancient bakery rooms were probably intended to be low and flat, providing essential working surfaces, like our modern kitchen work surfaces. Higher walls would have trapped and held all the smoke and ash generated during baking, making the small space intolerable to work in.

Experimental recipe

The emmer wheat and barley available to the ancient Egyptians contained very little gluten, the protein which gives modern breads their light, airy texture. The volume of our bread molds indicates that bread cooked in them must have been leavened.

Dough vats and finished bread.

There is a question about the presence of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) in ancient Egypt, but it is believed the species was not widely in use in Egypt until the Greeks brought it in. Emmer and barley were clearly the staple cereals but bread wheat does turn up occasionally and we have even found a little at Giza (though not enough to say that it was used for bread making at our site).

For our experiment, we leavened our bread with local, wild yeasts captured at Giza by Ed Wood, a retired pathologist, who has devoted much of his life to studying wild yeasts and the sourdoughs made from them. Ed tried various combinations of emmer and barley as described in his book World Sourdough Breads from Antiquity (Ten Speed Press, 1996).

Experimental results

We found that the bread baked best when covered with a preheated bedja, as shown in ancient tomb scenes. Without the cover, the bread did not bake through all the way.

It is possible, however, that we made the bread mold walls too thin and that the scenes depicting pots stacked over fire are actually showing a process to temper the pots to effect a non-stick surface or perhaps they were even firing the ceramics.

We think that the pots were set into the depressions and surrounded by charcoal. Then the bakers would light straw tinder around the pots. This might explain the greenish-gray accretion on the outsides of our ancient bread molds. We analyzed the accretion as vitrified phytoliths, the siliceous inclusions in plants and grasses.

Experimental taste test

Ed Wood and the experimental bread.

Experimental future

AERA patron, Dr. Nathan Myrhvold (physicist and master chef) is also interested in ancient breads and baking techniques. It is very clear from ancient depictions that the dough was poured into the bread molds. Nathan thinks that perhaps the dough was more like a biscuit or muffin batter than a spongy dough. We are looking forward to more experimental archaeology in ancient culinary arts. We would like to recreate the bakeries again to better answer some of the questions that are so important to understanding the diet that sustained the builders of the pyramids, because it is on just such basics of everyday life that great civilizations—and pyramids—were built.

Like so many issues surrounding the Giza Pyramids, it is often the little details, like how the ancient bakers made bread and fed thousands of workers, that are most important in understanding pyramid building and the most fascinating questions to us as archaeologists.