Latest News

Honoring Dr. Richard Redding

The entire AERA team mourns the loss of Dr. Richard Redding – our friend, mentor, and colleague – who passed away on May 22, 2023. We extend our deepest condolences to Richard’s loved ones and to everyone whose life he touched.

Richard started working with us at the “Lost City of the Pyramids” in 1991 and quickly became a valued team member, field school instructor, AERA board member, and our Chief Research Officer. He was an archaeologist who analyzed animal bone, but that doesn’t begin to encompass the depth and breadth of his research. Richard worked at sites across the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and the Americas, allowing him to put his results into the wider context of societies and economies of ancient cultures.

Over his thirty-two years of work at Giza, he amassed big data—literally millions of identifications of animal bone— that revealed striking patterns of status and diet in this city of pyramid builders. He left what may be the world’s largest corpus of archaeological faunal data compressed into the briefest of archeological periods (the fifty or so years of pharaohs Khafre and Menkaure). Richard also left an invaluable reference collection that we’ll make good use of by continuing his research and allowing other projects to access.

Richard was always a favorite teacher in our field schools for young Egyptian archaeologists. In addition to the “how,” he also taught the “why” of studying animal bone and inspired his students to always think critically. He embodied our field school motto: We are not looking for things, we are looking for information.”

Richard wrote many articles about his work with AERA, covering topics from the joy of bone smashing to finding enlightenment in a bowl of shorbet kawara (cow trotter soup). However, his most profound legacy may be the generosity and support he always extended to his colleagues and students. As one of his students wrote, “it is not often that one finds a teacher who always finds the time for listening.”

There is now a cadre of Egyptian zooarchaeologists he helped train and a special program of zooarchaeology at the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA) Training Center in Saqqara headed by his former student, Mohamed Hussein Ahmed. We’d like to share this excerpt from an article Mohamed and another student wrote in 2018 about their experience studying with Richard.

“The 2018 AERA-ARCE Field School training was a dream come true. It is important that people know that becoming an animal bone specialist in Egypt is not an easy thing. To even find such training in a university in Egypt is difficult, if not impossible. Both of us had an urgent need for this specialist training right now, as we are both working on our theses, and animal bone is a key component of our topics.”

“During our research, we would send emails to Dr. Redding asking for copies of articles or books, advice, opinions, or other help that we needed in our work, but it was not enough. It was hard to read the articles and understand them because they were full of difficult Latin terms and scientific abbreviations, and we needed help just to understand the specialist language. We told Dr. Redding we would be eager to have in-depth training, and he worked to make it possible during this year’s excavation season.”

Read the full article about their studies with Richard, Learning Animal Bone.

Khufu’s 30-Year Jubilee: Newly Discovered Pieces of a Puzzle

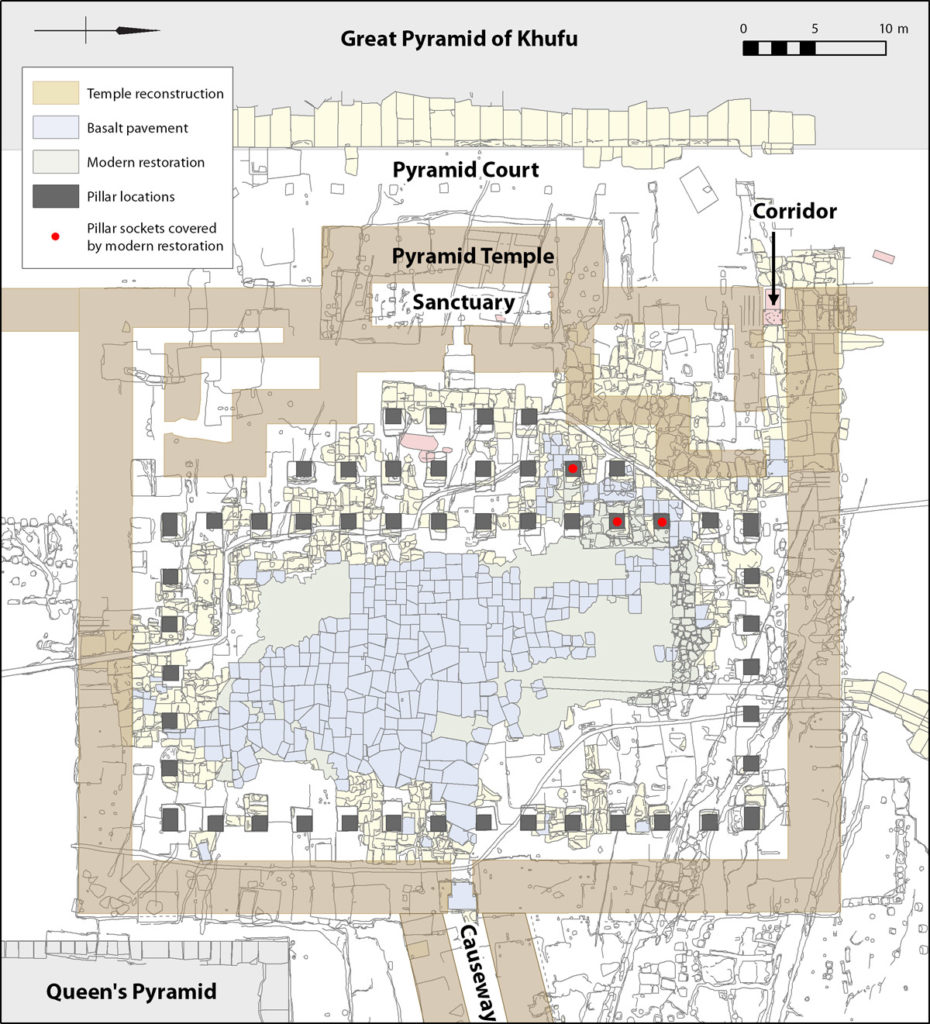

Sometime after Lauer mapped the temple, but certainly before the modern asphalt road was laid down, the basalt pavement of the open court underwent “restoration” with displaced stones from the pavement and gray cement. This restoration comprises some 40% of the “island” of pavement that remains. It covered three of the pillar sockets (highlighted in bright red, below).

Ashraf Mohedein, General Director of Giza, gave us permission to remove the restoration over the three sockets, so we could complete our documentation. Underneath, we found sandy debris. As we removed it, we were surprised to find limestone pieces with remains of relief-carved decoration in each socket. These pieces must come from the inner walls around the court. It appears that ancient material filling these pillar sockets was never removed before being covered. It makes us wonder whether more unexcavated material lies below the rest of the restoration.

There can be no mistaking the delicate, low relief as that of Khufu’s time, known from several other fragments1 found nearby or in the core of the Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty pyramid that Amenemhet I built at Lisht some 600 years later.

The face of one piece (facing page), a fragment 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) long, retains exquisite low relief of shrines and a row of typical Egyptian five-pointed stars with traces of paint, and a row of booths patterned after Predynastic reed “tent shrines,” lined up for a special festival called Sed—a celebration of a king’s 30-year jubilee that renewed his physical and magical power.2 As part of the ceremony, people erected temporary booths with shapes iconic of Upper and Lower Egypt. They housed images of local town gods. So that he could celebrate jubilees forever in the Afterlife, King Djoser built a set of Sed Festival tent shrines in his Step Pyramid complex.3 They are dummy buildings, like a sacred Universal Studios stage set, built here for magical effect. From a dais at the southern end, the king came and went to the shrines of local deities, or else they came to him, so that he could interlace his renewed vital force throughout the Two Lands.

Two of the four fragments found during the excavation and clearing of the temple that began in 1939 also belong to Khufu’s Sed jubilee. One shows the king, minus his head, enthroned in a kiosk, wearing a ceremonial Sed Festival cloak. Another shows Khufu striding, wearing the crown of the North with a particular scarf draped over his shoulder.4

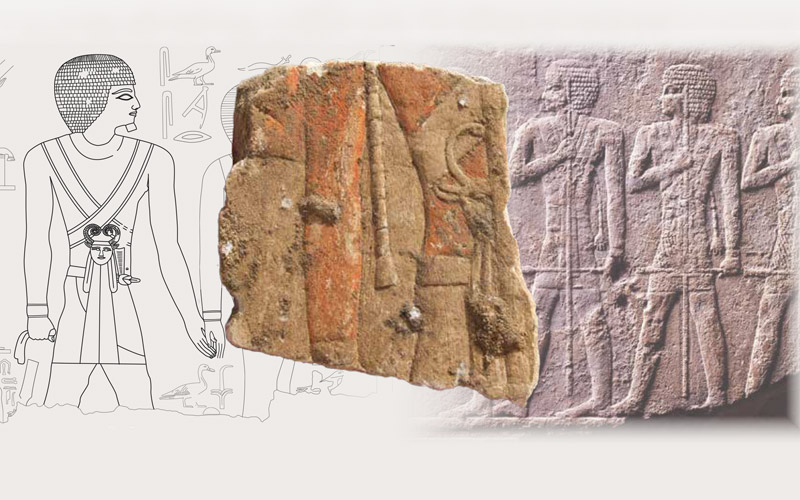

We found yet another fragment of Khufu’s jubilee (see Figure 1). It shows the torso and arm of a man wearing a sash hung with an emblem of the goddess Bat—a female face with cow ears and horns that curve inward toward one another. In later times, craftsman made sistra in Bat’s image. This “harness-like arrangement of crossed straps…with sistrum pendant”5 (the Bat emblem) featured a counterpoise, which we see in our fragment as a braided rope ending in a tassel, hanging between the arm and the small of the man’s back. The front-forward, cow-eared face of Bat is similar to common depictions of the cow-goddess Hathor, the mother of Horus (although Hathor’s horns curve in and then outward). Eventually, in the minds of the Egyptians, Bat and Hathor merged. The edge of a thick staff, held vertically, shows along the right edge of the piece.

In temple and tomb scenes, Egyptian artists labeled men wearing this assemblage as Kherep Ah, “Controllers of the Palace.” They are among the attendants to the king’s Sed jubilee. We see three of them on one of the many fragments of Old Kingdom temple scenes placed, for some reason, into the Middle Kingdom Pyramid of Amenemhet I at Lisht (see figure ??? right). In this fragment, each Controller wears the double crossed sash of Bat. They carry a kherep scepter in one hand and hold a tall, vertical staff in the other. They approach one of the rituals of the Sed Festival, in which a goddess named Meret cheers the king as he performs a ritual run to demonstrate his vitality. Hans Goedicke, who published the Old Kingdom reliefs from the Amenemhet I Pyramid (now in the Metropolitan Museum—MMA—in New York), ascribed the scene fragment showing the Controllers, along with a dozen other scene fragments, to the Sed tableau of none other than Khufu.6 He believed they came from the walls of the Great Pyramid upper temple or valley temple. He also assigned 14 other fragments to Khufu’s pyramid temple or valley temple. Six of these fragments actually bear parts of Khufu’s name in a cartouche.

We might then expect a match between the Bat emblems and Palace Controllers on the MMA piece and our newly discovered piece. But details don’t quite match. The counterpoise and tassel on ours and the MMA piece are different; the MMA Controllers wear their Bat emblems higher and hold their staffs vertical, while our staff seems at an angle. Dorothea Arnold wrote that, on the basis of the height and style of the MMA pieces, they must come from a temple of Khufu’s father, Sneferu, perhaps the hurriedly finished temple of his North Pyramid at Dahshur,7 which once featured two fine limestone shrines with Sed Festival scenes.

Any king, we suppose, could have his artists carve Sed jubilee scenes in his pyramid temple (or, later, in the 5th Dynasty, in his sun temple), whether or not he approached thirty years on the throne. The scenes magically ensured perpetual jubilees in the Afterlife. Dates in Khufu’s final years on the throne, discovered only in the last several years, suggest Khufu was, in fact, approaching his 30-year jubilee, but that he may have just missed it, at least in this world. The highest known dates for Khufu include the year after his 13th “cattle count,” discovered in 2013 in the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri.8 Egyptologists believe this Old Kingdom accounting for taxation took place every two years, so this would be Khufu’s regnal year 26–27. In 2016, the Japanese team from Waseda University published another unequivocal date, the 14th census (or “Occasion”) Month 1 of the season Shemu (“Harvest,” our spring-early summer). They found four examples of this graffito from the western of two rock-cut pits along the south side of the Great Pyramid, which they are excavating in order to salvage Khufu’s second wooden funeral ship. A regular, biennial “cattle count” would make this Khufu’s regnal year 28–29. The boats, which probably served as royal hearses, were placed in these pits at the time of Khufu’s funeral—the name of his successor, Djedefre, was also found in the graffiti from the pits. So, this date must be Khufu’s last “Occasion.”

Figure 1: In the center, a fragment of painted, carved relief discovered this year in the Great Pyramid Temple. The person depicted is a “Controller of the Palace,” indicated by the sash and emblem of the goddess Bat, a female face with cow’s ears and inward-curving horns. On the left the Bat emblem is worn by a son of Khufu on a reused relief fragment from the Amenemhet I Pyramid at Lisht, which may have originally been in one of Khufu’s or Sneferu’s temples. On the right an Old Kingdom relief fragment from Lisht shows three Palace Controllers wearing the sash and emblem of Bat. (Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Figure 2: Block with painted and relief-carved decoration showing booths lined up for the Sed Festival, traditionally a king’s jubilee of 30 years of rule, above a black band studded with stars.

Figure 3: Relief-carved fragment showing the back of a pleated kilt and hand holding a “key of life”—or ankh (left) and a relief fragment showing the head of a Horus falcon (right).

1. Flentye, L., “The Mastabas of Ankh-haf (G7510) and Akhethetep and Meretites (G7650) in the Eastern Cemetery at Giza: A Reassessment,” In The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor, Vol. 1, edited by Z. Hawass and J. Richards, Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities, pages 291–308, 2007. This and other publications on Giza can be downloaded for free at the Digital Giza Library website. Arnold, D., “23. Scenes from a King’s Thirty-year Jubilee;” “38. King Khufu’s Cattle;” “41. Head of a Female Personification of an Estate,” In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pages 196–198, 222–223, 226, 1999.

2. Frankfort, H., Kingship and the Gods, Chicago: University of Chicago, pages 79–99, 1948/1978.

3. Lauer, J.-P., “Note complémentaire sur le temple funéraire de Khéops,” Extrait des Annales du Service des Antiquités XLIX, Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1949; Reisner, G. A., and W. S. Smith, A History of the Giza Necropolis, Vol. II: The Tomb of Hetep-heres, the Mother of Cheops, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, pages 4–5, figs. 5–6.

4. Lauer, J.-P, Fouilles à Saqqara, La pyramide à degrés, Vol. 1, Cairo: Service des Antiquités del’Égypte, plate IV, 1936.

5. Smith, W. S., A History of Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom (2nd edition), London: Oxford University, pages 317, 320, fig. 191, 1949. A sistrum is a rattle, a percussion instrument.

6. Goedicke, H., Re-used Blocks from the Pyramid of Amenemhet I at Lisht, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.

7. Arnold, D. “23. Scenes from a King’s Thirty-year Jubilee,” In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, page 196, 1999. This can be downloaded for free from the Met Publications website.

8. Tallet, P., Les Papyrus de la Mer Rouge I: “Journal de Merer (Papyrus Jarf A et B),” Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 6, pl. I, 2017. See also Stille, A., “The World’s Oldest Papyrus and What It Can Tell Us About the Great Pyramids,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015.

This article was originally publised in our member newsletter, the AERAGRAM.

Join AERA now to help support our ongoing excavations in Egypt and you will receive these publications as soon as they are published.

Field Season 2022: The Soccer Field starts to reveal its secrets!

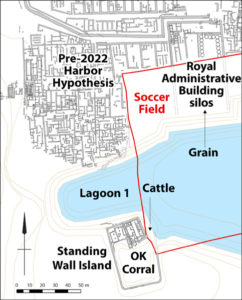

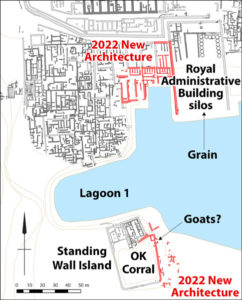

For many years we’ve thought Lagoon 1, the low-lying area at the southern end of the Lost City (Heit el-Ghurab) site, was once an ancient harbor that was used to deliver supplies to the city via the Nile.

For many years we’ve thought Lagoon 1, the low-lying area at the southern end of the Lost City (Heit el-Ghurab) site, was once an ancient harbor that was used to deliver supplies to the city via the Nile.

To the north of this proposed harbor, we found a series of large silos in the Royal Administrative Building in 2001. This is where grain was stored before it was turned into bread and beer to feed the pyramid workers.

To the south, we discovered the Standing Wall Island. In 2011, we found this compound contained a large, enclosed open area with a paperclip-like entrance that formed a chute. This enclosure seemed like it could be a stockyard where cattle were held, before being butchered to provide meat for the pyramid workers. We even started calling it the OK (Old Kingdom) Corral.

However, the corral’s actual entrance, along with the southern half of the silo building and most of the proposed harbor, ran under a modern soccer field, leaving us unable to see a large and crucial portion of our site.

This year we got permission to start excavating the old soccer field and we hoped to finally prove our harbor and corral hypotheses. But when we went to “ground truth” the corral entrance, we found something unexpected!

This year we got permission to start excavating the old soccer field and we hoped to finally prove our harbor and corral hypotheses. But when we went to “ground truth” the corral entrance, we found something unexpected!

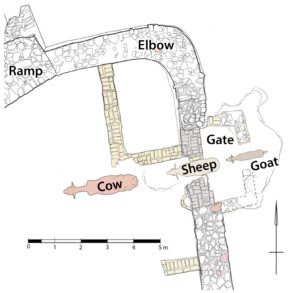

When we excavated the northeastern corner of the OK Corral that was previously under the soccer field, we found the wall formed an “elbow,” which turned and attached to a ramp at the north end of the corral. Near the elbow was a small gated opening, not the large open chute we had expected to find.

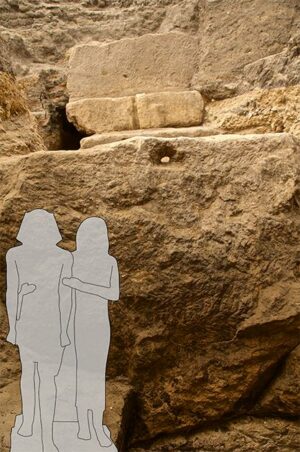

Could cattle have still come through this gate into the enclosed area? Though the entrance was originally 2.9 m wide, it looks like it was almost immediately narrowed to 0.85 m, and then again down to 0.56 m.

While it’s possible that smaller cattle could get through, it would be a tight fit. At this point an animal pen is still the best explanation for the enclosure, but was it meant for cattle?

While it’s possible that smaller cattle could get through, it would be a tight fit. At this point an animal pen is still the best explanation for the enclosure, but was it meant for cattle?

The Lost City was in its heyday during the reigns of Khafre and Menkaure, the builders of the Second and Third Giza Pyramids. When Menkaure died, he left his pyramid and temples incomplete. Though his successor, Shepseskaf, completed the monuments, he moved away from Giza to build his own tomb at Saqqara.

Our new excavations show the OK Corral’s enclosure wall was actually a late addition to the building. With only a smaller workforce left behind at Giza after Menkaure’s death, is it possible the people who remained started to receive mostly sheep and goats, lower status meat than cattle? And that the corral was remodeled with a new gate for smaller livestock?

How many and what type of animals the pyramid workers ate may seem like a small detail, but it’s details like this that ultimately help us piece together the lives of the people who built the pyramids and find out what happened to them once the Egyptian state’s focus shifted elsewhere.

How many and what type of animals the pyramid workers ate may seem like a small detail, but it’s details like this that ultimately help us piece together the lives of the people who built the pyramids and find out what happened to them once the Egyptian state’s focus shifted elsewhere.

Our motto is that we are not looking for things, we are looking for information. So we’ll follow the facts wherever they take us when we return to the Soccer Field area.

The full story of our recent work at the Soccer Field area and the Menkaure Valley Temple will be covered in future AERAgrams and our Annual Report.

Join AERA now to help support our ongoing excavations in Egypt and you will receive these publications as soon as they are published.

2021 Year in Review

This holiday season we are grateful for all of our members who’ve given us the opportunity to continue our research in Egypt. Thanks to you, we are back in Giza and hard at work on three back-to-back field projects.

We are so excited to be able to share this update from the field with you. Your membership or end of year donation will help ensure that 2022 will be our busiest and most exciting year yet!

We have three major field projects we will be working on through 2022

We began this year’s fieldwork by digging pilot trenches in the soccer field that covers the southeastern part of the “Lost City of the Pyramids.” We’ve been waiting more than 20 years to see what is under the soccer field. Preliminary data from these trenches, along with new information from Pierre Tallet’s work at Wadi el-Jarf, hints that an undiscovered palace and harbor for the 4th Dynasty pyramid-building kings may be buried here!

We began this year’s fieldwork by digging pilot trenches in the soccer field that covers the southeastern part of the “Lost City of the Pyramids.” We’ve been waiting more than 20 years to see what is under the soccer field. Preliminary data from these trenches, along with new information from Pierre Tallet’s work at Wadi el-Jarf, hints that an undiscovered palace and harbor for the 4th Dynasty pyramid-building kings may be buried here!

After a short break for the holidays, we will be returning to oversee the demolition of the soccer field and begin a major excavation of the buildings that remain untouched underneath. We are excited to once again work with young Egyptian archaeologists and have the opportunity to share with them our methods of systemic archaeology and site recording. We will also be working with a film crew from National Geographic to document and share our work as we search for the “Palace of Khufu.”

Our second project this year was a return to the Menkaure Valley Temple where we have now explored the entire western third of this massive temple, including areas that were previously unexcavated. Temple walls towered 3m (10 feet) over us as we worked!

We also continued exploring the “Thieves Hole,” where George Reisner found the famous Menkaure dyad statue. He thought more statues were to be found even deeper in the hole. It is now filled with ground water, but more statue fragments keep coming up as we dive toward the bottom, more than 15 feet under the temple floor. We look forward to continuing our work here next year to see what else we find.

For our third project, thanks to a generous grant from the American Research Center in Egypt, we will be working with Dr. Zahi Hawass at the Great Pyramid Temple to expand the walkway we previously built around the Pyramid Temple and install new signage to inform tourists about this important site.

We will also begin a conservation project to consolidate and replace part of the 1940’s restoration of the black basalt pavement of the pyramid temple court. When we previously took up two small patches of this “restored” pavement, we found new fragments of finely carved and painted scenes that originally adorned the pyramid temple’s walls. This year we will certainly find more!

We also have two major publications coming out in 2022

On January 11, Pierre Tallet and Mark Lehner’s new book The Red Sea Scrolls: How Ancient Papyri Reveal the Secrets of the Pyramids will be published. The discovery of the Red Sea Scrolls―the world’s oldest surviving written documents―was one of the most remarkable moments in the history of Egyptology and changed what we know about the building of the Great Pyramid at Giza. In this book, Tallet and Lehner narrate this thrilling discovery and explore how the building of the pyramids helped create a unified state, propelling Egyptian civilization forward.

We are also putting the finishing touches on a catalogue of all artifacts from AERA’s 34 years of excavations. Ancient artisans fashioned the tools that built the great pyramids and supported its workers from bits of stone, metal, clay, pottery, and bone. We are excited to share this everyday Old Kingdom toolkit with you online in the months to come. In the meantime, we hope you enjoy a preview of some of these fascinating tools (along with some holiday cheer) in the image at the top of this email.

Happy holidays and best wishes for the new year from Mark Lehner & the entire AERA team!

Our members and donors support our excavations in Egypt, field school training, conservation efforts and much more. Members also receive printed copies of our AERAgram newsletters and annual reports as soon as they are published. Join AERA and help us explore further!

Watch Decoding the Great Pyramid online

In “Decoding the Great Pyramid,” AERA’s Mark Lehner, Claire Malleson, Glen Dash, and Richard Redding join Salima Ikram and Pierre Tallet to discuss the latest research into how the Great Pyramid was built and how building it transformed Egyptian society. Now PBS is making this and some of their other favorite NOVA episodes available online for free.

How did the ancient Egyptians engineer Khufu’s Great Pyramid at Giza so precisely? Who were the thousands of laborers who raised the stones and how were they housed and fed? And how did mobilizing this colossal labor force transform Egypt? Watch “Decoding the Great Pyramid” on PBS.com to find out.

2020 Year in Review

This year we are especially grateful to our members who’ve given us the opportunity to continue our work throughout this challenging year. Thanks to their support we were able to adapt to changing conditions and continue to search for clues to the development of Egyptian civilization and help to preserve Egypt’s heritage for the future.

- While our spring excavation season was cut short, we were able to explore the Menkaure Valley Temple‘s (MVT) foundations and finish excavating its southwestern side.

- We documented and helped conserve the remains of the Great Pyramid Temple and are improving the visitor experience at this important but often overlooked site.

- We are finishing work on the Objects Publication Project documenting the everyday items used by the people who constructed the Giza pyramids.

- We published the beautifully illustrated and researched Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis museum catalog, which we’ve made freely available to download.

- Dr. Mark Lehner was able to share our work with AERA members and others in an online lecture on The People Who Built the Pyramids.

Looking Forward to 2021: From Discovery in the Field to Publication

Installing the walkway at the Great Pyramid temple

While we’re grateful for the work we were able to get done this year, like everyone we hope for the chance to do even more in the upcoming year. Our 2021 plans include:

- the grand opening of the Great Pyramid Temple’s new visitor walking route,

- the publication of Dr. Lehner’s definitive work on the Sphinx and a new book documenting our work at the Heit el-Ghurab (HeG) and Khentkawes Town sites,

- returning to the Menkaure Valley Temple to begin excavating the storage rooms in the northwest, an area of the site unseen since Reisner’s work over 100 years ago,

- a remote sensing project to “see” what is underneath the soccer field that has overlain the southeastern corner of the HeG site since its discovery, followed by removal of the modern buildings and targeted excavations of the area.

We hope you will continue to follow our work and we look forward to sharing new discoveries with you in 2021. We are truly grateful to everyone who helps make our research possible. We hope you will become a member or make a donation and help us continue our work in Egypt.

Sincerely,

Mark Lehner

President, Ancient Egypt Research Associates

AERA members will receive information on our 2020 & 2021 excavation seasons in our AERAgram newsletters. Become an AERA member to receive your copy, enjoy all of our member benefits, and help support our work in Egypt!

Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis

We are delighted to announce the publication of Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis, by AERA archaeologist Aude Gräzer Ohara. This detailed catalog of the remarkable collection of artifacts from the Mît Rahîna museum is now freely available to students, scholars, and museum visitors from around the world.

We are delighted to announce the publication of Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis, by AERA archaeologist Aude Gräzer Ohara. This detailed catalog of the remarkable collection of artifacts from the Mît Rahîna museum is now freely available to students, scholars, and museum visitors from around the world.

Click here to download a PDF copy of Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis.

The museum of Mît Rahîna sits on archaeological remains in the heart of the Memphite ruin field and displays a substantial and remarkable collection of monuments, including several unique pieces that deserve to be more widely known. With this book we hope to offer insight into the museum’s collection and context, as well as the history and excavation of Memphis, Egypt’s ancient capital city.

This important research work stems from our Memphis Development Project (MDP), a joint effort with the University of York, funded by a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and AERA’s members and donors. The MDP grew from deep roots: AERA’s long history of field schools for Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities Inspectors, including Beginners, Advanced, Salvage Archaeology, and Scientific Analysis and Publication.

In 2011 and 2014 we ran field schools at Memphis, the first major field archaeology projects there in 20 years. During this time, we saw first hand that Memphis urgently needed the world’s attention once again as modern development and neglect threatened this ancient capital, so important to Egyptian and world history. Responding to this urgent need, as part of the MDP we cleaned seven archaeological sites within Memphis and installed pathways between each. Our field school students also created documentation for tour guides and visitors and new bilingual signage to make the site more accessible and understandable to visitors. We also renovated and enhanced the museum and as part of the documentation process, recorded and researched its collection.

The fruit of that work is Treasures from the Lost City of Memphis, the first volume to provide a comprehensive presentation of both the museum’s history and a catalog of its treasures, richly illustrated and researched, and presented against an informative backdrop of the excavation history of Memphis.

For all of you who helped with your support, we are proud of your trust in AERA and our work. If you aren’t already an AERA member, we invite you to become a member to enjoy all of our member benefits and help support our work in Egypt!

2019: Our Year in Review

Thanks to the support of our members and donors, in 2019 we were able to bring together specialists from around the world to search for answers about the origins and development of Egyptian civilization and help preserve Egypt’s heritage for the future.

Returning to the Menkaure Valley Temple (MVT) and the Great Sphinx of Giza

We returned to the MVT to excavate its western side, unseen since George Reisner discovered the famous statue of Menkaure and Queen in 1910, where we made some intriguing discoveries.

Along with Dr. Zahi Hawass and the Glen Dash Foundation, we conducted a geophysical survey of the Sphinx Temple using ground penetrating radar. We also collaborated with Yukinori Kawae and a Japanese team to carry out 3D recording of the Sphinx by drone, photogrammetry, and laser scanning.

Preserving & Interpreting Egypt’s Heritage: From Monuments to Everyday Life

Thanks to 2019-2020 grants from ARCE, we’ve begun work on two conservation projects. The Great Pyramid Temple Project aims to conserve what remains of Khufu’s pyramid temple and to promote greater visitor understanding of the pyramid complex as a whole.

The AERA Objects Publication Project will create a freely accessible archive of data about the everyday items used by the individuals involved in the construction of the Giza pyramids and mortuary cults and will offer scholars a unique insight into Old Kingdom economy, administration, technology, and daily life.

Sharing our Work with a Worldwide Audience

Our work in Egypt was featured in several new documentaries this year. Decoding the Great Pyramid examined the latest research into how the Great Pyramid was built and how building it transformed Egyptian society, while an episode of CNN’s Inside Africa gave an in-depth look into our ongoing work at the MVT.

A statue fragment from the MVT

Looking Forward to 2020: Deeper into the MVT and the Search for Khufu’s Palace

In early 2020, we’ll return to the Menkaure Valley Temple and begin to dig even deeper to see what new information remains to be found in its deepest, unseen levels.

At the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders, most of what we’ve found so far dates to the reigns of Khafre and Menkaure, but somewhere underneath lies an even older phase of the site. This year we’ll continue our search for the location of Khufu’s pyramid town and palace, Ankh Khufu, which we’ve found tantalizing clues about in the oldest levels of the site and the Kromer area dumps, as well as in the Wadi el-Jarf papyri.

In this holiday season, we are truly grateful to everyone who helps make our research possible. We hope you will become a member or make a donation and help us continue our work in Egypt. We look forward to sharing more discoveries with you in 2020!

Sincerely,

Mark Lehner

President, Ancient Egypt Research Associates

AERA members will receive information on our 2019 & 2020 excavation seasons in our AERAgram newsletters. Become an AERA member to receive your copy, enjoy all of our member benefits, and help support our work in Egypt!

New Findings from Menkaure Valley Temple

AERA’s 2019 Field Season Report: New Findings from the Menkaure Valley Temple

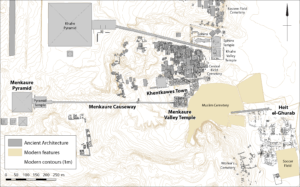

Figure 1: The central-southeastern Giza Plateau showing the location of the Menkaure Valley Temple where we worked during 2019.

The First and Second Temples

During our 2019 Field Season, we returned to the Menkaure Valley Temple (MVT), an area crucial to our understanding of the overall settlement of the Giza Plateau. We believe that when people abandoned the Heit el-Ghurab (HeG) settlement (also known as the Lost City of the Pyramid Workers) they resettled near the Khentkawes Town (KKT) and MVT. The nature of these sites then changed from infrastructures for large royal works to service centers for the cults of the deceased kings.

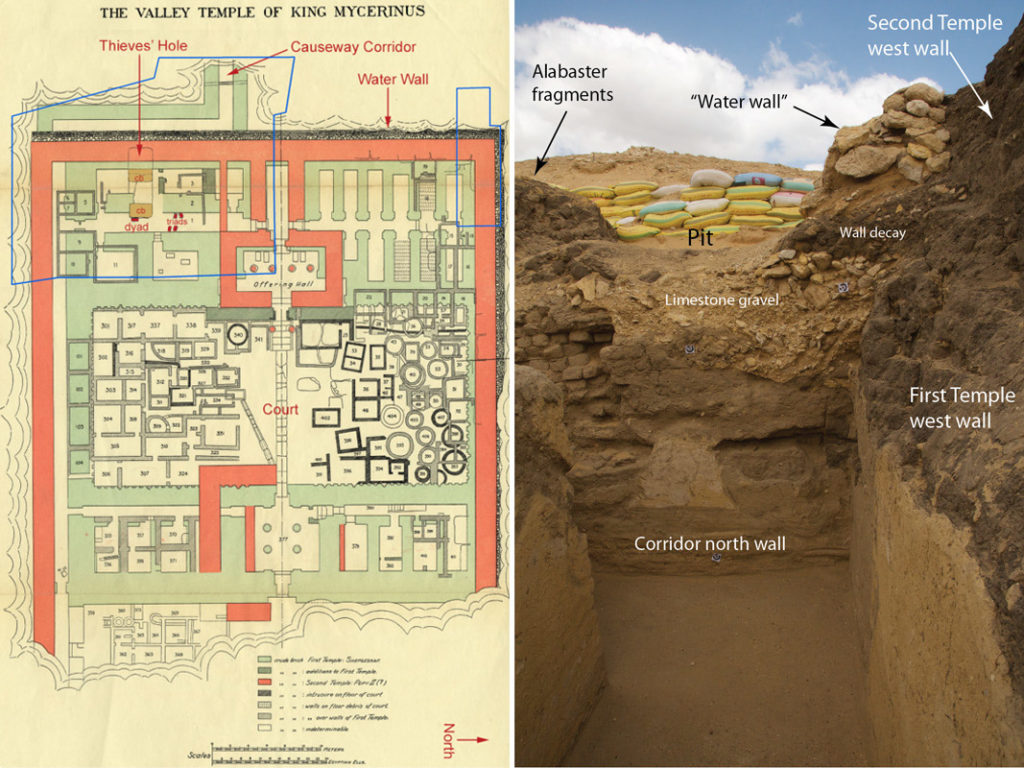

George Reisner excavated the MVT between 1908 and 1910, but he never saw the whole temple exposed in phase, so his plan of the temple is reconstructed from separate exposures. It was clear to Reisner that he had two major periods: an earlier mudbrick “First Temple” (shown in green on Fig. 2) completed by Menkaure’s successor Shepseskaf and a later “Second Temple” (shown in orange on Fig. 2) built over 200 years later, probably under king Pepi II. Reisner found evidence that a desert flash flood streamed down the northern side of the causeway washing out the center of the First Temple west wall and destroying the portico and offering hall. After this event, the MVT was abandoned. Eventually, people returned and rebuilt the outer wall of the Second Temple roughly over what survived of the outer wall of the First Temple. Late in the occupation of the Second Temple, people built a fieldstone “Water Wall” against the base of the outer wall as protection against further flash floods.

Figure 2: On the left is Reisner’s (1931: plan VIII) multi-phase map with AERA’s annotations. Light green: First (4th Dynasty) Temple, orange: Second (6th Dynasty) Temple, hachured gray: an intermediate phase (5th Dynasty), black: latest domestic structures, blue lines: AERA’s 2019 excavation, cb = core block. On the right is a view from our 2019 excavations inside the MVT after Reisner’s backfill was removed.

Removing Reisner’s Backfill

A good part of our work this year went into removing and examining the deep sand and spoil that Reisner dumped into the back of the MVT and around the surrounding area as he excavated the central court. This central court area was filled with domestic structures, including many bins and granaries, which were built over time on top of each other across the court and up and over the “First Temple” walls (see Figure 2). This area was both architecturally complex and rich in material culture. A short distance north of Reisner’s excavation, we found concentrated deposits of Egyptian alabaster mixed with sand overburden, which extended north beyond our limit of excavation. These spoil deposits were rich in pottery, flint tools, animal bones, ash, charcoal, worked stone (included a diorite beard from a royal statue), pigment, wood, metal, clay sealings, and nearly 100 kg of alabaster statue fragments. Some of the alabaster fragments showed parts of hieroglyphic texts, while others showed traces of blue paint. This deposit is probably where Reisner’s workers sorted the material they found in the court. These finds were overlooked or deemed unimportant in Reisner’s time, but today there is much that we can learn from them.

Figure 3: Finds from dry sieving Reisner’s dumps from the excavations of the MVT court settlement. Left: Bones, blades, and a bit of copper. Right: Sealing fragment impressed with a seal that includes the cartouche name of Menkaure. Inset: Menkaure’s cartouche name excerpted from a sealing found in the HeG.

We have yet to fully examine most of the material we retrieved from Reisner’s backfill. However, animal bone and flint tools appear to be, by far, the most abundant material. If this material did come from the apartments in the southern side of the court, the people who stayed there cut a lot of meat. Are we finding the remains of food ritually offered to Menkaure and then consumed by people in the service of his temple? Further work in our lab may help us find out.

Descending into the Thieves’ Hole

After we had removed Reisner’s backfill, our attention then turned to what he called the “Thieves’ Hole.” This is where Reisner discovered the Menkaure dyad, before being stopped from going further by the rising ground water. Given our limited time and resources, we focused on removing Reisner’s fill within his retaining walls to reach the bottom of the hole, which gave a valuable cross-section of the stratified architecture of the temple.

As we descended we were astounded by the great depth of this part of the temple and the massiveness of the First Temple walls. We found two large limestone “core blocks,” so-called because they were meant to form the cores of the walls, which the builders would later sheath in hard granite. This is evidence that Menkaure wanted to build a stone temple, like Khafre’s Valley Temple, but the stonework stopped, probably when he died, and the temple was completed in mudbrick.

Figure 4. An outline of the dyad statue in the approximate position where Reisner’s team found it standing upright and practically undamaged on January 18, 1910. View to the west.

Further to the east inside the Thieves’ Hole, we found another large limestone core block. In front of this block is where Reisner discovered the famous nearly life-sized statue of Menkaure and a woman, probably the queen mother, standing upright and nearly undamaged (except for a chip off the king’s beard). This dyad statue, on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, is one of the most magnificent sculptures in world art history. Reisner’s explanation that the Thieves’ Hole had been “dug by treasure-hunters of the Moslem Period” and that the dyad was “apparently thrown into the hole by the treasure-hunters before they began the next hole on the west” did not add up as we now looked at the evidence 109 years later. Why would robbers leave the dyad until later and why would they sink it so deep under the temple floor? How did the dyad remain so relatively undamaged if it was thrown in?

A New Theory Emerges

Our archival research and this season’s excavations have led us to realize that Reisner did not actually find the dyad in the Thieves’ Hole at all, but in a deeper, older hole, that someone dug in ancient times a little farther east. AERA senior archaeologist Dan Jones came up with this important finding from a meticulous review of Reisner’s published report, unpublished diary, and photographs, all available at The Giza Archives.

On January 16, 1910, Reisner wrote in his diary “(n)ext to the thieves’ hole…there is another hole filled with such debris (yellow gravel) that it also must be a thieves’ hole.” In all later reports Reisner conflated the two conjoined holes, but a close study of his photographs along with our new excavation leads us to believe the Thieves Hole and the “dyad hole” are indeed different features. The older dyad hole appears to have been started from the surface of the ruins of the First Temple. That is, someone dug this hole down into the crushed limestone foundation of the First Temple during or after it fell into ruin, perhaps soon after the flash flood destroyed the sanctuary.

It now appears that the Menkaure dyad may have been buried long before the Thieves’ Hole was dug and that this older dyad hole was intentionally dug expressly for placing the undamaged statue upright, for safe keeping deep inside the temple foundations. Why this was done, and who and what the dyad represents, must await further discussion. When we return to the deep end of the MVT for our 2020 Field Season, we hope to find more answers.

Our 2019 Season was made possible thanks to the generous support of Dr. Walter Gilbert, the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), and AERA’s members and donors.

AERA members will receive more information on our work at the MVT in future AERAgrams. Join AERA now to help support our ongoing excavations in Egypt and you will receive these publications as soon as they are published.

Watch AERA’s 2019 excavations at Menkaure Valley Temple

A CNN crew joined our team in March to document what it was like working on the Menkaure Valley Temple in Giza. This is the first video footage from the western part of the Temple, which until this year had been buried under sand since George Reisner last saw it 100+ years ago.

The video documents some of our recent finds, details our approach to archaeological science, and interviews some of the incredible team of people working with us from Egypt and around the world. We are so happy to be able to share this video with our members!

CNN’s Inside Africa documented our 2019 excavation as part of a program on Egyptian archaeology that also features recent finds at Saqqara and ARCE’s field school program.