Heit el-Ghurab

Wall of the Crow gate from Vyse, 1840.

There is a massive, ancient stone wall that stands a few hundreds yards south of the Sphinx. But because it lay partially buried and overshadowed by the pyramids and Sphinx, tourists have hardly noticed it. Known locally as the Wall of the Crow (Heit el-Ghurab in Arabic) it is 200 meters (656 feet) long, ten meters (32.8 feet) high, and ten meters thick at the base.

The Wall is the northwest border of a tract of low desert that we at first designated Area A and later became known as The Lost City of the Pyramids or Heit el-Ghurab (named after the wall’s Arabic name). When we first started our excavations at the Lost City site, we suspected that the Wall of the Crow dated to the Old Kingdom 4th Dynasty (2575-2465 BC), like the Giza Pyramids and the Sphinx, but we did not know why the Egyptians built it. Evidence suggested that they never completed the mammoth undertaking. They never dressed the masonry to produce a finished face to the structure, as was their standard practice with pyramids, tombs, and temple walls.

After further excavations, we can now say for certain that the Wall of the Crow was built as part of our 4th Dynasty (2551-2472 BC) complex and the archaeology has led us to form some ideas as to its function.

Gateway to the sacred?

Wall of the Crow gate.

The great gateway in the Wall of the Crow may be one of the largest gateways from the ancient world. It has been visible for the last 4,500 years and yet very little has been written about it. Once we cleared away a thick, sandy overburden, we discovered what an impressive structure the gate is—2.5 to 2.6 meters wide (about 8.5 feet or five ancient Egyptian cubits) and about 7 meters (23 feet) high. Because the base of the Wall is more than 10 meters thick, the gate is actually a short tunnel. The ancient roadway going through the gate was paved with worn or abraded ceramic fragments and laid out with a subtle camber—the sides slope down and away from the center—a common feature of ancient roads.

Along the length of the south side of the wall east of the gate, we cleared a ramp-like slope on the surface of an embankment of limestone chips. This mason’s debris must have been waste from building the wall. It also may have been used as a ramp to drag the massive lintels up over the top of the gate. After placing the stones, the builders left the debris immediately in front of and inside the gate. Upon this debris, traffic formed a path that slopes down 2 to 3 meters (6.56 to 9.84 feet) from north to south. The path passes through the gate to a broad terrace formed of compact sandy masons’ debris that extends at least 30 meters north of the gate.

Function

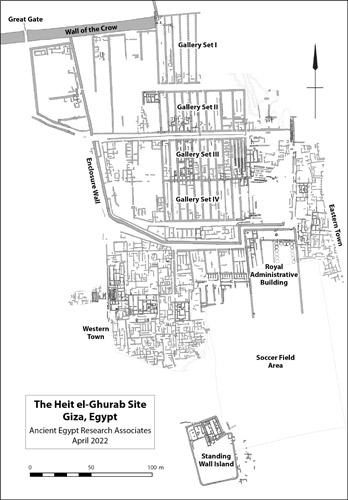

A plan of the Lost City of the Pyramids site. Note the gallery at the east end of the Wall of the Crow.

Why did the builders put so much effort into an immense stone structure that was not part of a pyramid complex nor connected to other structures at Giza? The builders shaped and hauled a huge number of massive blocks to form something more like a dike than a wall. In contrast, the rest of our settlement is mostly built of mud brick or broken stone from the nearby Maadi Formation. The Wall may have separated the sacred precincts of the pyramid plateau from the precincts in which the workers lived. The Enclosure Wall that bounds the Gallery Complex on the west nearly abuts the Wall of the Crow, and the regulated passageways out of the settlement—especially Main Street, the principle axis—led right to the massive gateway in the Wall of the Crow.

In 2002 we found clear evidence that the Gallery Complex (at least Gallery Set I) predated the Wall of the Crow. Until then we were not certain where the Wall ended on the east. The eastern end of the Wall slumped in two layers of large stones, the result of collapse and robbing in late antiquity (we found Late Period burials under the lowest layer of toppled stones). The remains of the gallery walls were about waist to chest-high at the eastern end of the Wall, but about three meters to the east (10 feet), the gallery ruins were cut down to ankle level in a great depression. A massive deposit of granite dust and chips filled this big depression. The granite was from large-scale work nearby, possibly cuttings from the granite casing on the Menkaure Pyramid. But what force cut this depression through the mud brick gallery walls well before the end of the 4th dynasty occupation on our site? Perhaps a flash flood.

Flood control?

Geoarchaeologist Karl Butzer, who studied the environmental history of our site, believes that the 4th Dynasty Egyptians built their settlement on the outwash of a wadi, a stream bed that occasionally carried heavy floods running off the high desert. The Wall of the Crow stands just to the south of the stream bed and could have served to deflect the floodwaters.

East end of the Wall of the Crow.

If the inhabitants built the massive stone wall for protection against desert flooding, why not extend it across the northern end of the whole Gallery Complex? Perhaps they thought that the thick, mud brick northern wall of Gallery Set I could withstand the wadi floods. The Wall of the Crow might then have been meant to protect the western flank of the Gallery Complex. In fact, an earlier settlement here might actually have succumbed to flash floods. In the lowest layers, those predating the Gallery Complex, we found settlement debris—mud bricks, pottery fragments, and limestone rocks—mixed with mud and pebbles washed down from the natural gravel in the high desert. We continue to look for evidence to support a hypothesis that the Wall may have served as flood-control to protect the workers settlement.

Sacred structure

Late Period burials sprawl in a large cemetery across the northwestern portion of our site, with grave upon grave cut into the Old Kingdom deposits. Toward the eastern end of the Wall of the Crow, the graves increase in density like the epicenter of a galaxy.

Burial at Wall of the Crow.

The Late Period (747-525 BC) residents of nearby towns must have considered the area around the Wall of the Crow as sacred ground. The burials extend right up to the east end of the Wall, with some of the dead interred in the sand above rocks that tumbled from the Wall. These burials post-date the collapse of the eastern end of the Wall. Caches of animal bone that we encountered in the same sand layer as some of the nearby Late Period burials are another sign of the Wall’s sanctity. One cache included two skulls—from a bovine and a smaller animal, possibly a goat. Another cache contained two cattle skulls. In the spring of 2000, when we began clearing the southern side of the Wall of the Crow near the east end, we encountered a third cache—a bovine skull and a Late Period amphora tucked into a niche between the blocks of the Wall.

Child burials

Next to the eastern end, the percentage of child burials is higher than in other areas: 60% compared with, for example, 27% in a nearby square. Many of these children were adorned with jewelry and amulets, while adult burials contained no grave accoutrements. We do not yet understand the significance of these special child burials.

The Wall of the Crow today

Archaeologists working at the Wall of the Crow.

The area around the Wall of the Crow is still a burial ground. An Islamic cemetery engulfs the west end of the Wall and a Coptic Christian cemetery lies just south of it. During funerals, the deceased is carried in a procession through the great gate in the Wall. It is possible that this part of our site was a burial ground from late Roman to early Christian times. The first Muslim graves, the tombs of sheikhs (learned Muslim men), were built north of the west end of the wall. Both cemeteries—Coptic and Muslim—have wells; water sources are often associated with sacred traditions.

The Wall of the Crow is also still associated with fertility even today. Until recent years, women hoping for children would squat near a nail (a bronze survey peg pounded into the Wall by a surveyor many years ago), and then walk around the raised limestone blocks seven times. Through the millennia that the Wall of the Crow has laid half-buried, it has maintained its sacred aura and perhaps become even more mystical. We certainly look in awe upon this massive structure poised between the worlds of the living and dead, both ancient and modern.