By Edward Johnson (Archaeological Conservator), Günter Heindl (Architect/archaeologist), Ashraf Abdel Aziz (Archaeologist), and Brian V. Hunt

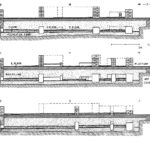

ETH before reconstruction

Trying to visualize living space from an architectural plan can be challenging. Walking around in a 3-dimensional space provides a different perspective on the use of that space.

Over a period of more than ten years, AERA archaeologists have exposed and analyzed a number of architecturally varied structures at the Giza pyramid settlement. In the autumn of 2005, AERA initiated a project to not only conserve but to reconstruct one architectural unit of the ancient Egyptian settlement we are excavating.

Of three candidate test structures, which varied in form and content, we selected the building with the smallest surface area and volume. The structure sits among other ancient Egyptian housing at the eastern reach of our concession, an area we appropriately call Eastern Town.

Our test object, Eastern Town House (ETH), is an almost completely intact house foundation with clear evidence of remodeling during the period in which it was inhabited, during Egypt’s 4th Dynasty (ca. 2575-2465 BC).

Dan Housel and Emma Hancox excavated ETH in 2004 and recorded six phases of ancient remodeling. The layout of the house, the objects found, and attested to activities of a family household, like houses at the Middle Kingdom pyramid-town at Lahun.

ETH included an enclosure wall, courtyards, a vestibule separating public and private areas, a main room with a sitting bench, and a sleeping niche.

There was an area for grinding and storage facilities, pottery jars set in the floor, and a small circular granary. The second set of courtyards could be entered both from the front and the back of the house. Here we found traces of baking and cooking.

The spaces inside ETH would have been crowded and bustling, with no provision for the kind of individual personal space taken for granted by many cultures today.

Conservation challenges

There is little in the Egyptological publications about mud brick conservation, although a number of archaeological missions have carried out extensive conservation projects. Our colleagues from other missions gave us valuable input as we surveyed existing mud brick conservation near Giza, Abu Sir, Dahshur and Abu Roash.

Every conservation project is unique, due to the local environmental exposure and the construction materials used in building. The ancient inhabitants built Eastern Town House of mud brick, with a few elements of undressed stone and possibly wooden columns. Ancient mud brick presents great challenges to conservation due to its fragility.

Options

We needed to use a conservation technique that was best suited to the environment and structures at Giza.

Enclosing ETH in a protective structure was less than ideal for aesthetic and practical reasons. Such an enclosure would also have limited effectiveness. Capping the ancient walls with a new layer of mud brick was inadequate because it might actually accelerate the deterioration. The original walls would still be exposed to rain—water being mud brick’s greatest enemy. Chemical consolidants arry their own problems and limitations, penetrating only the surface of a wall, creating stress with the raw core.

Backfilling ETH and burying the structure would effectively protect the ancient mud bricks and provide a base for reconstruction.

Backfilling and reburying

The reason these ancient walls survive to our time is because they were buried and protected beneath the sand. We chose to rebury Eastern Town House to recreate its pre-excavation environment.

To isolate our reconstruction from ground moisture, we backfilled the walls beneath a deep layer of clean sand upon which we constructed a platform of mud brick. The raised, mud brick platform provided a base for the reconstructed house.

As we built a framing wall around ETH, workers backfilled directly over the ancient structure, allowing us to reconstruct ETH at the same site and with the same orientation as the original.

The platform

The platform had to be strong and stable to support the reconstructed house. We examined several options for building the platform, including single- and double-layered solutions.

The single-layered options may have been adequate, but caution led us to carefully consider the pressure the walls would be subject to with being walked upon or bearing the weight of the reconstructed walls.

We chose to lay a double-layered mud brick platform directly on the sand. We bonded the bricks with sand and mortar, and covered with a plaster made with Nile clay, chaff, and water.

We constructed the lower layer with stretchers, headers, and half-bricks arranged relatively irregularly (long, continuous joints decrease stability). We laid The second layer in a herringbone pattern. We now had a solid base on which to construct new walls.

Material

Proper techniques require that everything we do in conservation and reconstruction must be reversible (which is a problem with chemical consolidants). Future archaeologists and researchers must be able to undo what we have done so that they can study the original structure underneath.

Best bricks

AERA archaeologist, Ashraf Abdel Aziz, is creating a typology of ancient mud bricks. It is interesting to note that he has identified differences in bricks from buildings across the Giza Plateau. Ashraf brought his knowledge to our reconstruction project and was involved in our analysis of other conservation sites in Egypt.

We wanted to use brick of similar material and of the same approximate size as the brick originally used in the construction of the Eastern Townhouse (28 x 14 x 8 centimeters). We estimated that the platform base, framing wall, and house walls of ETH would require approximately 24,500 bricks.

Salah, our longtime guard at the site, of somewhat advanced age, had agitated from the beginning for an opportunity to make bricks. When he persisted, we acquiesced in order to raise the production rate.

To our delight, he made the best bricks of all, using a somewhat different technique from all the other brick makers. He put the mixture in the brick-forms without re-watering, the wet mortar, packed it down forcefully by hand, and added a little water on the top surface to smooth it down.

He made a very well-formed brick (without any temper other than sand) with clean sharp edges, completely filled ends, and without any melting or slumping from excess water.

He was a bit slower than the younger brick makers, but his product was so superior, that we continued to rely on him in this capacity until we finished.

The walls

We used varying heights of walls to demarcate different parts of the house complex. The completed reconstruction has:

- four courses of bricks for features like the silo

- six courses for the courtyard walls

- eight courses for the central building—the core house

There are enough substantial walls left in the settlement to allow us a clear understanding of the ancient construction techniques. We built our new walls in exactly the same way that the old walls were built.

We filled the wide joints with brick chippings and mortar. The corner bricks of each layer were measured and adjusted to the same height using an automatic level.

As the brick layers rose we incorporated doorways. We built a limestone threshold for the main entrance in the west wall based on examples we have excavated at the site. For the entrance of the private quarters, we installed an exact copy of a stone door socket that we excavated in situ.

The floor

To level the floor, we used a layer of coarse plaster followed by a finer plaster made of sieved Nile clay, sieved sand, straw, and water. We left the plaster to dry for a few days with a watchman on duty each night to protect the floor from damage by feral dogs.

Reconstructed features

Finally we added the grain silo, the bed, two wall extensions, and what may have been a grinding vat.

The ancient grain silo was originally constructed as an ellipsoid, because a full circle would have left too little room for people to squeeze between the silo and the adjacent walls. We reconstructed the silo to reflect this interesting example of how the occupants adapted the structures of everyday life to the tight spaces in the house.

Based on comparative evidence, we estimate ETH could have housed four to eight people (perhaps more). The house had only one bed platform, which raises the question of how many people actually lived, slept or otherwise utilized the house.

Conclusions

We may surmise, based on what we know about ancient Egyptian society and households that Eastern Town House was a crowded place by the standards of housing in modern, developed societies but perhaps typical for ancient Egypt. Our reconstruction revealed a little urban estate that felt much more roomy than the footprint we mapped during excavation.

Within the confines of the house and courtyards, the cooking and craft work in and around ETH would have made for an often smoky place. Inhabitants would have constantly negotiated space with other people, stored goods, and animals, including sheep, goats, and possibly a pig or two.

While the original structure is now unavailable for viewing, Eastern Town House is now protected from the elements. The reconstruction represents an extremely faithful model of what this structure really looked like and how it functioned. Our techniques are entirely reversible and future researchers can undo what we have done.

Reconstructing Eastern Town House and building other test walls on the Giza settlement site help us understand the living spaces and construction methodology employed by the ancient pyramid builders. The test walls allow us to monitor erosion—caused by wind, rain, and rising moisture—before proceeding with further conservation.

We look forward to doing more of this kind of work at the city of the pyramid builders. Incorporating interdisciplinary, experimental archaeology into our mission broadens our interpretation of the reality of the ancient Egyptians and reinforces our methodology.