What can color tell us about an ancient culture? Possibly a lot, according to Dr. Laurel Flentye. She’s doing a comparative study of the pigments found by AERA archaeologists at the Lost City of the Pyramids and the nearby tombs of the Fourth Dynasty (the Eastern Cemetery and the G1S Cemetery).

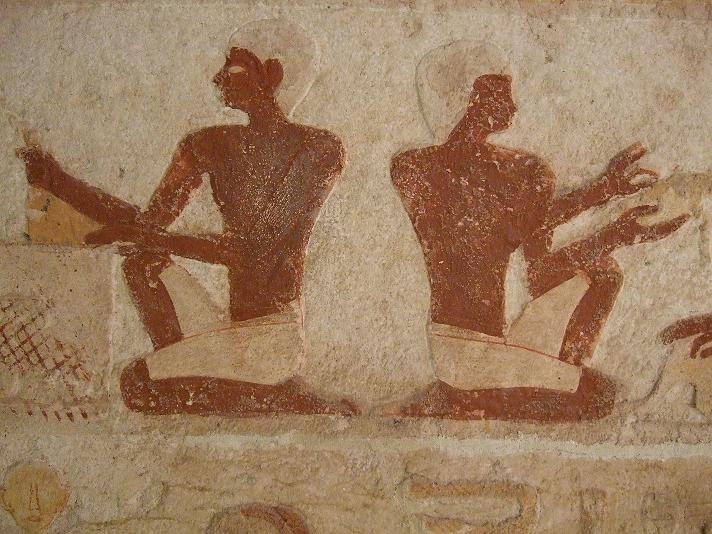

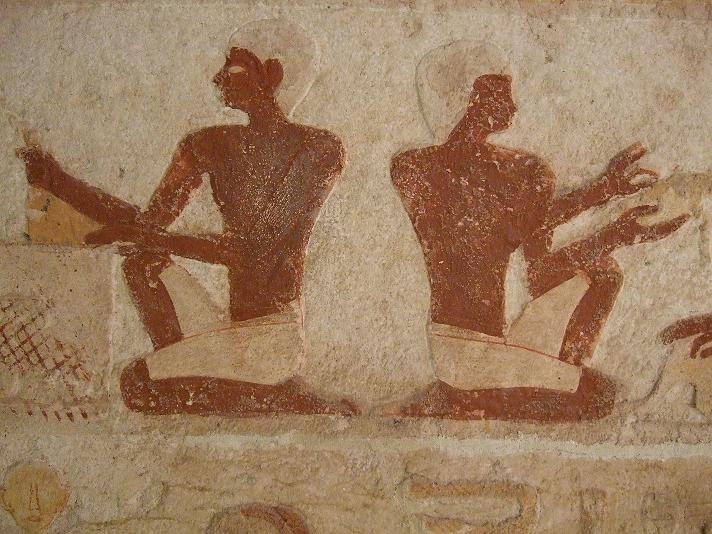

Scene in the tomb of Meresankh III.

Goal

There is little published on ancient Egyptian pigments, particularly those of the Fourth Dynasty. One of Laurel’s goals is documentation. Some of the tombs that still show color may one day be denuded due to time and pollution. It’s important that the pigments are recorded in context so we can try to understand the practical and religious considerations that played a part in the choice of color.

Why did the ancient Egyptians use certain colors? Are colors, materials, and schemes used in the Giza tombs different than those used on objects and surfaces at the pyramid settlement? Who were the artisans who made and used these colors? These are some of the questions Laurel is asking.

The Egyptian palette was limited.

The Egyptians used a fairly restricted palette for decoration: red, yellow, blue, green, black, and brown. They made most colors using minerals, such as red ochre or hematite for red, and yellow ochre for yellow. Egyptian blue was a synthetic pigment created through various manufacturing phases that included copper silica and calcium. Green, also a synthetic material, consisted of wollastonite, although it has been suggested that some greens may be degraded forms of blue. Black was made of carbon black.

Red and yellow must have been produced on a massive scale, as they were used most frequently. Ancient Egyptian men were usually depicted with reddish skin and women with yellow skin. Both colors were also used in the decoration of wall surfaces.

Laurel with painted marl plaster from the pyramid settlement.

In her research at Giza, Laurel found some unusual colors, not usually associated with the Egyptian palette. One was pinkish, salmon-color.

“You can’t really understand tomb reliefs unless you look at the statues. What were the artisans doing, for example, in terms of the leg musculature or portraiture?” The artisans working on the royal pyramid complexes with their relief decoration and statuary must have interacted with the artisans decorating the tombs in the surrounding cemeteries. Are there parallels?

Last year, Laurel spent time in the basement of the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square. She looked at thirty-one Fourth Dynasty statues of Khufu, Djedefre, Khafre, and Menkaure to better understand the stylistic formations of royal art during the period when the Giza Pyramids were built. That work is ongoing.

Artisans

“Artisans are one of the unknown quantities [from ancient Egypt]. Who created this [art and decoration]?” In the tomb of Meresankh III at Giza, two artisans are named. Sometimes it’s possible to see a single hand at work, especially when, for example, the text on one wall is the same as on another wall.

Still vibrant after 4,500 years.

How did the ancient artisans work? In the tomb of Duaenra (late Fourth Dynasty), which is partially unfinished, it appears the artisans began in the middle of a wall and worked towards the corner. I saw an engraving on a false door in the Western Cemetery where the artisan had started the inscription from the bottom up but never finished it. More investigation may reveal detailed work patterns.

Laurel will publish the results of her research when it’s complete. It’s another fascinating piece of the multidisciplinary puzzle that AERA is putting together to better understand the people who built the most magnificent monuments of the ancient world.

We’d like to thank Dr. Zahi Hawass for permission to photograph and use images from the tomb of Meresankh III, and Dr. Mahmoud Afify and Mrs. Reda Mousa for providing access to the tomb.

Brian Hunt

What can color tell us about an ancient culture? Possibly a lot, according Dr. Laurel Flentye. She’s doing a comparative study of the pigments found by AERA archaeologists at the Lost City of the Pyramids and the nearby tombs of the Fourth Dynasty (the Eastern Cemetery and the G1S Cemetery).

Scene in the tomb of Meresankh III.

Goal

There is little published on ancient Egyptian pigments, particularly those of the Fourth Dynasty. One of Laurel’s goals is documentation. Some of the tombs that still show color may one day be denuded due to time and pollution. It’s important that the pigments are recorded in context so we can try to understand the practical and religious considerations that played a part in the choice of color.

Why did the ancient Egyptians use certain colors? Are colors, materials, and schemes used in the Giza tombs different than those used on objects and surfaces at the pyramid settlement? Who were the artisans who made and used these colors? These are some of the questions Laurel is asking.

The Egyptian palette was limited.

The Egyptians used a fairly restricted palette for decoration: red, yellow, blue, green, black, and brown. They made most colors using minerals, such as red ochre or hematite for red, and yellow ochre for yellow. Egyptian blue was a synthetic pigment created through various manufacturing phases that included copper silica and calcium. Green, also a synthetic material, consisted of wollastonite, although it has been suggested that some greens may be degraded forms of blue. Black was made of carbon black.

Red and yellow must have been produced on a massive scale, as they were used most frequently. Ancient Egyptian men were usually depicted with reddish skin and women with yellow skin. Both colors were also used in the decoration of wall surfaces.

Laurel with painted marl plaster from the pyramid settlement.

In her research at Giza, Laurel found some unusual colors, not usually associated with the Egyptian palette. One was pinkish, salmon-color.

“You can’t really understand tomb reliefs unless you look at the statues. What were the artisans doing, for example, in terms of the leg musculature or portraiture?” The artisans working on the royal pyramid complexes with their relief decoration and statuary must have interacted with the artisans decorating the tombs in the surrounding cemeteries. Are there parallels?

Last year, Laurel spent time in the basement of the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square. She looked at thirty-one Fourth Dynasty statues of Khufu, Djedefre, Khafre, and Menkaure to better understand the stylistic formations of royal art during the period when the Giza Pyramids were built. That work is ongoing.

Artisans

“Artisans are one of the unknown quantities [from ancient Egypt]. Who created this [art and decoration]?” In the tomb of Meresankh III at Giza, two artisans are named. Sometimes it’s possible to see a single hand at work, especially when, for example, the text on one wall is the same as on another wall.

Still vibrant after 4,500 years.

How did the ancient artisans work? In the tomb of Duaenra (late Fourth Dynasty), which is partially unfinished, it appears the artisans began in the middle of a wall and worked towards the corner. I saw an engraving on a false door in the Western Cemetery where the artisan had started the inscription from the bottom up but never finished it. More investigation may reveal detailed work patterns.

Laurel will publish the results of her research when it’s complete. It’s another fascinating piece of the multidisciplinary puzzle that AERA is putting together to better understand the people who built the most magnificent monuments of the ancient world.

We’d like to thank Dr. Zahi Hawass for permission to photograph and use images from the tomb of Meresankh III, and Dr. Mahmoud Afify and Mrs. Reda Mousa for providing access to the tomb.

Brian Hunt