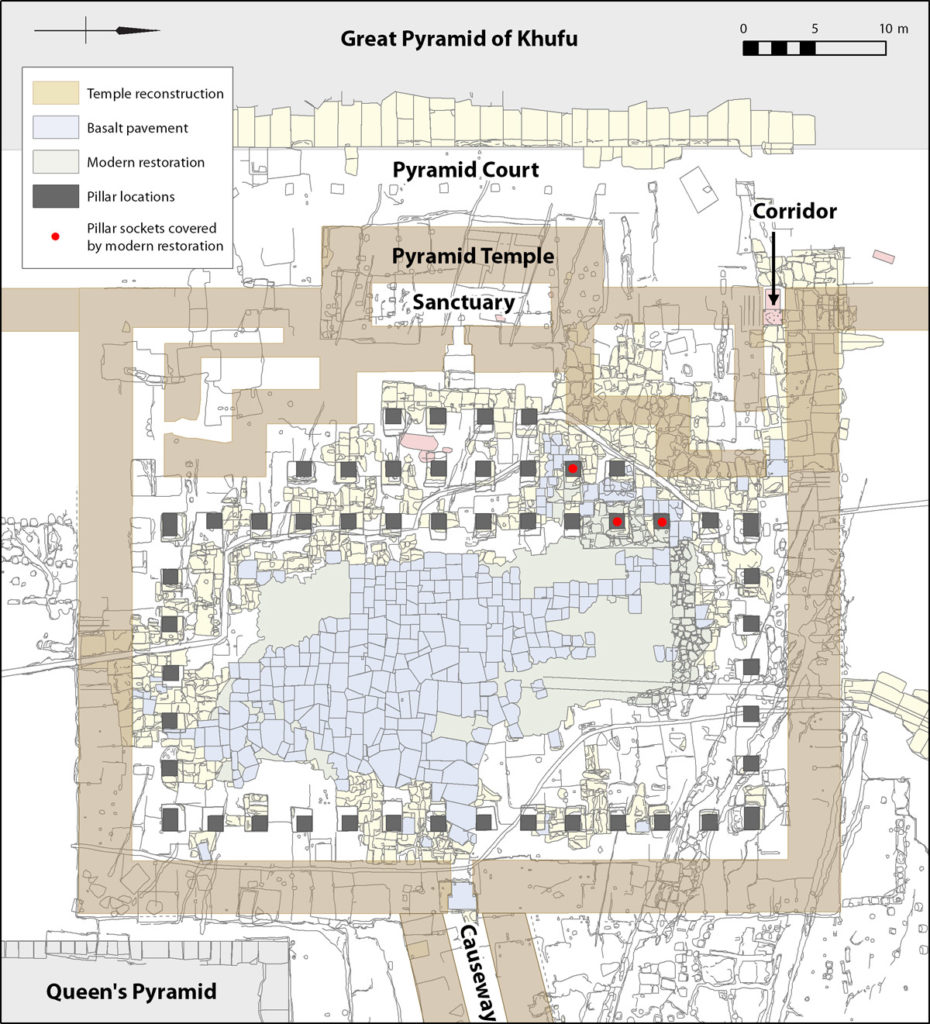

Sometime after Lauer mapped the temple, but certainly before the modern asphalt road was laid down, the basalt pavement of the open court underwent “restoration” with displaced stones from the pavement and gray cement. This restoration comprises some 40% of the “island” of pavement that remains. It covered three of the pillar sockets (highlighted in bright red, below).

Ashraf Mohedein, General Director of Giza, gave us permission to remove the restoration over the three sockets, so we could complete our documentation. Underneath, we found sandy debris. As we removed it, we were surprised to find limestone pieces with remains of relief-carved decoration in each socket. These pieces must come from the inner walls around the court. It appears that ancient material filling these pillar sockets was never removed before being covered. It makes us wonder whether more unexcavated material lies below the rest of the restoration.

There can be no mistaking the delicate, low relief as that of Khufu’s time, known from several other fragments1 found nearby or in the core of the Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty pyramid that Amenemhet I built at Lisht some 600 years later.

The face of one piece (facing page), a fragment 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) long, retains exquisite low relief of shrines and a row of typical Egyptian five-pointed stars with traces of paint, and a row of booths patterned after Predynastic reed “tent shrines,” lined up for a special festival called Sed—a celebration of a king’s 30-year jubilee that renewed his physical and magical power.2 As part of the ceremony, people erected temporary booths with shapes iconic of Upper and Lower Egypt. They housed images of local town gods. So that he could celebrate jubilees forever in the Afterlife, King Djoser built a set of Sed Festival tent shrines in his Step Pyramid complex.3 They are dummy buildings, like a sacred Universal Studios stage set, built here for magical effect. From a dais at the southern end, the king came and went to the shrines of local deities, or else they came to him, so that he could interlace his renewed vital force throughout the Two Lands.

Two of the four fragments found during the excavation and clearing of the temple that began in 1939 also belong to Khufu’s Sed jubilee. One shows the king, minus his head, enthroned in a kiosk, wearing a ceremonial Sed Festival cloak. Another shows Khufu striding, wearing the crown of the North with a particular scarf draped over his shoulder.4

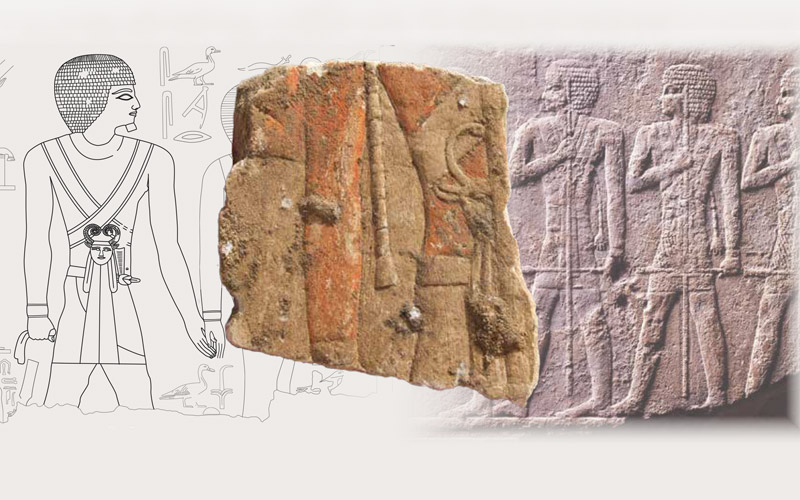

We found yet another fragment of Khufu’s jubilee (see Figure 1). It shows the torso and arm of a man wearing a sash hung with an emblem of the goddess Bat—a female face with cow ears and horns that curve inward toward one another. In later times, craftsman made sistra in Bat’s image. This “harness-like arrangement of crossed straps…with sistrum pendant”5 (the Bat emblem) featured a counterpoise, which we see in our fragment as a braided rope ending in a tassel, hanging between the arm and the small of the man’s back. The front-forward, cow-eared face of Bat is similar to common depictions of the cow-goddess Hathor, the mother of Horus (although Hathor’s horns curve in and then outward). Eventually, in the minds of the Egyptians, Bat and Hathor merged. The edge of a thick staff, held vertically, shows along the right edge of the piece.

In temple and tomb scenes, Egyptian artists labeled men wearing this assemblage as Kherep Ah, “Controllers of the Palace.” They are among the attendants to the king’s Sed jubilee. We see three of them on one of the many fragments of Old Kingdom temple scenes placed, for some reason, into the Middle Kingdom Pyramid of Amenemhet I at Lisht (see figure ??? right). In this fragment, each Controller wears the double crossed sash of Bat. They carry a kherep scepter in one hand and hold a tall, vertical staff in the other. They approach one of the rituals of the Sed Festival, in which a goddess named Meret cheers the king as he performs a ritual run to demonstrate his vitality. Hans Goedicke, who published the Old Kingdom reliefs from the Amenemhet I Pyramid (now in the Metropolitan Museum—MMA—in New York), ascribed the scene fragment showing the Controllers, along with a dozen other scene fragments, to the Sed tableau of none other than Khufu.6 He believed they came from the walls of the Great Pyramid upper temple or valley temple. He also assigned 14 other fragments to Khufu’s pyramid temple or valley temple. Six of these fragments actually bear parts of Khufu’s name in a cartouche.

We might then expect a match between the Bat emblems and Palace Controllers on the MMA piece and our newly discovered piece. But details don’t quite match. The counterpoise and tassel on ours and the MMA piece are different; the MMA Controllers wear their Bat emblems higher and hold their staffs vertical, while our staff seems at an angle. Dorothea Arnold wrote that, on the basis of the height and style of the MMA pieces, they must come from a temple of Khufu’s father, Sneferu, perhaps the hurriedly finished temple of his North Pyramid at Dahshur,7 which once featured two fine limestone shrines with Sed Festival scenes.

Any king, we suppose, could have his artists carve Sed jubilee scenes in his pyramid temple (or, later, in the 5th Dynasty, in his sun temple), whether or not he approached thirty years on the throne. The scenes magically ensured perpetual jubilees in the Afterlife. Dates in Khufu’s final years on the throne, discovered only in the last several years, suggest Khufu was, in fact, approaching his 30-year jubilee, but that he may have just missed it, at least in this world. The highest known dates for Khufu include the year after his 13th “cattle count,” discovered in 2013 in the Wadi el-Jarf Papyri.8 Egyptologists believe this Old Kingdom accounting for taxation took place every two years, so this would be Khufu’s regnal year 26–27. In 2016, the Japanese team from Waseda University published another unequivocal date, the 14th census (or “Occasion”) Month 1 of the season Shemu (“Harvest,” our spring-early summer). They found four examples of this graffito from the western of two rock-cut pits along the south side of the Great Pyramid, which they are excavating in order to salvage Khufu’s second wooden funeral ship. A regular, biennial “cattle count” would make this Khufu’s regnal year 28–29. The boats, which probably served as royal hearses, were placed in these pits at the time of Khufu’s funeral—the name of his successor, Djedefre, was also found in the graffiti from the pits. So, this date must be Khufu’s last “Occasion.”

Figure 1: In the center, a fragment of painted, carved relief discovered this year in the Great Pyramid Temple. The person depicted is a “Controller of the Palace,” indicated by the sash and emblem of the goddess Bat, a female face with cow’s ears and inward-curving horns. On the left the Bat emblem is worn by a son of Khufu on a reused relief fragment from the Amenemhet I Pyramid at Lisht, which may have originally been in one of Khufu’s or Sneferu’s temples. On the right an Old Kingdom relief fragment from Lisht shows three Palace Controllers wearing the sash and emblem of Bat. (Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Figure 2: Block with painted and relief-carved decoration showing booths lined up for the Sed Festival, traditionally a king’s jubilee of 30 years of rule, above a black band studded with stars.

Figure 3: Relief-carved fragment showing the back of a pleated kilt and hand holding a “key of life”—or ankh (left) and a relief fragment showing the head of a Horus falcon (right).

1. Flentye, L., “The Mastabas of Ankh-haf (G7510) and Akhethetep and Meretites (G7650) in the Eastern Cemetery at Giza: A Reassessment,” In The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor, Vol. 1, edited by Z. Hawass and J. Richards, Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities, pages 291–308, 2007. This and other publications on Giza can be downloaded for free at the Digital Giza Library website. Arnold, D., “23. Scenes from a King’s Thirty-year Jubilee;” “38. King Khufu’s Cattle;” “41. Head of a Female Personification of an Estate,” In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pages 196–198, 222–223, 226, 1999.

2. Frankfort, H., Kingship and the Gods, Chicago: University of Chicago, pages 79–99, 1948/1978.

3. Lauer, J.-P., “Note complémentaire sur le temple funéraire de Khéops,” Extrait des Annales du Service des Antiquités XLIX, Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1949; Reisner, G. A., and W. S. Smith, A History of the Giza Necropolis, Vol. II: The Tomb of Hetep-heres, the Mother of Cheops, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, pages 4–5, figs. 5–6.

4. Lauer, J.-P, Fouilles à Saqqara, La pyramide à degrés, Vol. 1, Cairo: Service des Antiquités del’Égypte, plate IV, 1936.

5. Smith, W. S., A History of Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom (2nd edition), London: Oxford University, pages 317, 320, fig. 191, 1949. A sistrum is a rattle, a percussion instrument.

6. Goedicke, H., Re-used Blocks from the Pyramid of Amenemhet I at Lisht, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1971.

7. Arnold, D. “23. Scenes from a King’s Thirty-year Jubilee,” In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, page 196, 1999. This can be downloaded for free from the Met Publications website.

8. Tallet, P., Les Papyrus de la Mer Rouge I: “Journal de Merer (Papyrus Jarf A et B),” Cairo: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 6, pl. I, 2017. See also Stille, A., “The World’s Oldest Papyrus and What It Can Tell Us About the Great Pyramids,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015.

This article was originally publised in our member newsletter, the AERAGRAM.

Join AERA now to help support our ongoing excavations in Egypt and you will receive these publications as soon as they are published.