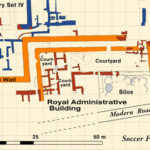

The thick, limestone foundation wall of a large, ancient building occupies the southeastern corner the Lost City site at Giza. This is certainly a royal complex.

It is 45 meters (147 feet) wide, extends more than 35 meters (115 feet) north to south, and disappears under a modern soccer field.

Evidence within the structure indicates 4th Dynasty inhabitants used this building for administration and storage. For convenience we call this the Royal Administrative Building (or RAB).

It may seem odd in this ancient culture that prized the durability of stone for its temples and royal tombs, and who believed their kings to be semi-divine, that the Egyptians built royal residences and associated buildings using mud brick. All of the palaces known from ancient Egypt were made of mud brick with stone details.

But temples were residences for the gods. Royal memorial temples were “Mansions of Millions of Years.” Royal compounds were just the earthly home for a temporal monarch.

There is evidence that pharaohs kept multiple households throughout the Nile Valley. Some Egyptologists believe that the three kings who built the Giza Pyramids might have had residences at Giza during construction.

Inside the RAB

Was the RAB part of a royal residence situated between the Eastern and Western Town? We are as yet unsure of all of the functions of the RAB, but we have ample evidence of storage and some kind of administration.

A prominent feature is the sunken court of round silos, each about five ancient Egyptian cubits (2.62 meters or 8.5 feet) in diameter. We found seven mud-brick silos and they continue under the soccer field.

This must have been the central storage for the dozens of bakeries associated with the Gallery Complexes. A trench from a parapet wall remains around the silos. It is possible that RAB workers could walk upon this wall and fill the silos through holes in the tops. When they needed grain, they could let it out from openings near the floor level.

In a series of small courts and chambers that we have excavated in the northwest corner of the RAB, we found sealings, the little fragments of fine, hard clay the Egyptians used to seal bags, boxes, jars, and doors.

Our excavations in the RAB yielded an unusually large numbers of these sealings, some with the royal names Khafre (2520-2494 BC) and Menkaure (2490-2472 BC). This is one of the largest collections of inscribed material anywhere on our site.

As of 2005, most of the RAB still lies beneath the modern Abu Hol Soccer Club. We have done subsurface sensing over the soccer field, and the data reveal what might be the southwest corner of the RAB, giving the building a total length of 100 meters (328 feet). We hope to excavate there when a new soccer field is built for the residents of the adjacent village.

Restricted access

Approaching the RAB from the west within the Gallery Complex, ancient occupants of the pyramid city would have walked along the southernmost of three main thoroughfares: South Street.

On the right, just before reaching the RAB, were a series of nine magazines (some of which may have been bakeries) divided by fieldstone walls. We call these the South Street Magazines. We found some of these chambers tightly packed with pottery, mostly bread moulds.

The southernmost block of galleries, Gallery Set IV, lay across South Street from the magazines.

At the northwest corner of the RAB, South Street was intentionally narrowed to less than one meter (3.28 feet), probably to restrict access to production and storage areas.

Separate roads

RAB Street appears to have been the major conduit between the Eastern and Western Towns. Traffic must have consisted of people on foot, possibly on donkeys, or even small herds of sheep and goat.

The Enclosure Wall strictly separated anyone passing through RAB Street from anyone moving down South Street inside the Gallery Complex. If the Enclosure Wall rose above head height, pedestrians on either side of it would not have been able to see each other.

Whatever the function of the Royal Administrative Building and the magazines, access to them was strictly controlled and restricted.

Who were these townspeople, moving west to east across our site? Did different classes of people use the two routes? Were they otherwise segregated in the settlement?

Wear patterns show that RAB Street was very well traveled. When people and animals rounded the northwest corner of the RAB, they habitually hugged the inside of the turn. This pedestrian traffic wore down the roadbed, creating a deeper pathway just at the base of the outer corner of the RAB wall.

At the same time, more refuse accumulated along the outside of the turn. The result was a roadbed that sloped down from NW to SE, into the corner, like a racetrack.

Ancient activity

Our excavations suggest diverse activities in the RAB. Clearly storage was a major function of the portion we have cleared so far.

Little balls of clay with finger marks and pieces pinched off might indicate sealing preparation, often evidence of administration. Sealings were used as security devices to prevent unauthorized opening of important goods or messages.

We found little mud tokens that might have been used as counters. They take various shapes including bread loaves and haunches of beef.

Bone points and rods found in the RAB were probably used for weaving and deposits in a small corridor yielded evidence of copper and alabaster workings.

An older complex underneath

In 2004 and 2005 we excavated down to a phase of architecture that existed before the inhabitants built the RAB. This consists of 14 rectangular chambers of various sizes flanked along the east by a long open court.

The RAB builders incorporated parts of the walls of the earlier complex into the new courts and chambers and partly demolished and covered the remains of the earlier walls.

Three small, rectangular chambers at the northern end of the older complex might have been magazines or storage chambers, approximately one by two meters (3.28 X 6.5 feet) in size. The magazine floors were littered with the following artifacts.

Northern magazine

- A spouted vessel.

- Red pigment.

- Red painted plaster fallen from a wall.

- Sandstone pieces (perhaps abraders).

- The broken end of a small saddle quern.

- Yellow ochre pigment from the tumble layer above the floor.

Middle magazine

- A limestone pivot socket.

- Parts of flat round bread baking trays.

Southern magazine

- A straight-rim jar.

- Three cylindrical jar stands.v

- A stone hammer.

- A lump of basalt.

- Pieces of worked flint.

- A pillow stone. The small, rectangular stones form a class of artifact with examples from across the site. We do not know their function.

Abandonment and demolition

Before the end of the 4th Dynasty, the RAB silos were cut through and partially demolished. Tons of broken stone from the wall around the sunken court toppled onto the ruined mud-brick silos. A significant quantity of this stone is granite, which is not native to Giza and must have come from Aswan.

In fact, there is evidence of substantial granite working both here and at the east end of the Wall of the Crow (WCE). The evidence at WCE was tons of granite dust, the byproduct of a great deal of stone finishing work. The granite in the area of the RAB shows signs of the initial stages of dressing large blocks: large flakes and chunks.

The collapsed stone filled the lower, sunken court of silos. The stone surface eroded into a level platform; late in the Old Kingdom, someone removed the collapsed stone along the west end of this platform and piled up a cairn over the corner of the sunken court.

A pit in the middle led down to a simple grave containing a child burial. This cairn, or funerary tumulus, contained some of the few late Old Kingdom pottery sherds that we have found across the site.

More to do

The RAB is one of many features at Giza that we have been privileged to help save. Workers from nearby riding stables had removed the protective ancient overburden right down to the surface of the ancient ruins.

One of our archaeologists, Ashraf Abd al-Aziz, is working on a typology of the mud bricks at our site. Already we see patterns indicating that our brick culture is very different than even that of the bricks at the nearby ancient town built for the cult of Queen Khentkawes.

What other functions did the royal house carry out here, in this great stone-walled enclosure between the Eastern and Western Towns? In the future, when the soccer field is moved, we look forward to learning more about the Royal Administrative Building.