The details of mapping the Sphinx

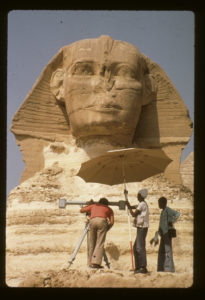

Ulrich Kapp and assistants talking stereo-pair photographs of the Sphinx with the photogrammetric camera.

Why map a statue? There is no way to understand a monument as complex as the Sphinx without examining in detail of all of its elements. This includes mapping the bedrock of the Sphinx, mapping the ancient and modern restorations, and mapping the associated temples in the Sphinx complex.

While clearing the Sphinx quarry down to bedrock for a subsurface mapping project, Zahi Hawass and Mark Lehner noted that there were ancient deposits that had never been excavated. Using modern archaeological methods, the team revealed cultural material from the time of the pyramids, including numerous pieces of 4th Dynasty pottery (2575-2465 BC), right up through the Roman occupation of Egypt (30 BC-395 AD).

During the work, Hawass and Lehner realized that the existing maps of the Sphinx were not very useful and that, in fact, there were no accurate maps of this important monument.

AERA’s story began with a project to map the Sphinx, with Dr. James Allen as Director and Mark Lehner as Field Director. Sponsored by the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) over a five-year period, the ARCE Sphinx Project produced the only existing large-scale maps of the Sphinx.

Intent

Sunset at the equinox suggests intentional alignment

The alignment and iconography of the Khafre monuments suggest a strong connection to the cult of the sun god, Re.

One of the significant alignments discovered during the Sphinx mapping project is that a line can be drawn from the Sphinx Temple’s east-west axis through an enigmatic box along the right side of the Sphinx. The line continues to the apparent south side of Khafre’s pyramid as it appears on the horizon when viewed from the Sphinx Temple.

Twice a year, on the equinoxes, the sun sets on this alignment and would have illuminated the Sphinx Temple sanctuary and cult statue if the builders had finished the temple interior. The setting sun would renew the power of the dead king and like him, enter the underworld where Re and Osiris are united.

The Sphinx’s alignment with the other Khafre monuments indicates a building program linked to beliefs around a solar cult.

Auguste Mariette made a small note during his excavations at the Sphinx in the 1850s that he had found a shattered statue of Osiris at the base of the Sphinx box.

Restorations

The southern elevation of the Sphinx as of 1979, produced by Ulrich Kapp of the German Archaeological Institute, with the masonry veneer color-coded by period by Mark Lehner.

Given the poor quality of the limestone from which the Sphinx’s lion body is cut, it’s not surprising that after many centuries the statue needed restoration, beginning in antiquity. Repair work began thousands of years ago and has continued throughout the statue’s history. Stone blocks of varying size have been used to encase the native rock of the Sphinx to restore its shape and protect it from further deterioration. The Roman restoration consisted of small brick-sized stones, which can still be seen in places. The Romans, however, used relatively soft white limestone that deteriorated badly.

The French engineer, Emile Baraize, carried out major excavations from 1926-1936. Baraize had reset much of the Roman stones that he found tumbled. Unfortunately, his 11 years of work were never published and many phases of architecture around the Sphinx were dismantled without proper documentation.

The soundest ancient restorations were those by the ancient Egyptians, who generally used durable masonry that developed a protective brown patina.

Looking between the forepaws of the Sphinx provides clues that help date the oldest repairs of the giant statue. There stand the remains of a small open-air chapel built by Thutmose IV. The centerpiece of the chapel’s back wall is a 15-ton stela dated to 1401 BC: the famous Dream Stela.

The Dream Stela commemorates Thutmose IV’s accession to the throne by relating a story of his path to kingship. He tells of a day as a young prince (not the crown prince) when he was hunting in the vicinity of the Sphinx and napped in the shadow of the statue’s head.

The Dream Stela

While he slept, the Sphinx, as the embodiment of the sun god, appeared in a dream and offered the throne of Egypt if Thutmose would clear the sand from around the statue’s body.

The Dream Stela offers compelling evidence for dating the oldest restoration work to Thutmose IV, about 1,100 years after Khafre built the Sphinx. The limestone blocks framing the stele are consistent with the restoration on the Sphinx’s paws and chest.

The Dream Stela is a reused doorway lintel from Khafre’s mortuary temple. In fact, the pivot sockets on the back of the stela match sockets in the threshold of Khafre’s temple. In addition, our mapping project provided evidence that some of the masonry cladding used to restore the Sphinx came from the walls of Khafre’s pyramid causeway.

The friable native stone of the Sphinx sanctuary still erodes daily. The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (previously called the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities) carried out a major restoration program in the 1980s and 1990s. They used the ARCE Sphinx Project maps to ensure that replacement masonry matched the earlier appearance of the statue.

The importance of accurately mapping ancient monuments is evident in the toll that time and the elements take on them. Today, all along the Nile Valley, the Supreme Council of Antiquities is in a race to save antiquities from pollution, rising ground water, the impact of tourism, and the natural deterioration that occurs over time. Some monuments now exist only in the maps and records made by archaeologists. What we don’t record, we lose forever.