*The next installments of our field blog will be a long story in four parts, by AERA Sealings Team Member and Managing Editor Ali Witsell. Before you read these next installments, we suggest you read John Nolan’s introductory sealings blog from the beginning of the season, for a refresher course on sealing terminology.

In a way, ancient clay sealings are a lot like postage stamps. To a philatelist, stamps encapsulate much about the society that they represent, be they a first-day issue 1847 5-cent Benjamin Franklin, an Egyptian 1879 5-piastre gray Sphinx and Pyramid, or a US 2013 Johnny Cash Forever stamp. A perusal of the offerings available in any US post office will give you a quick snapshot of that which American society values today: civic history and the battle for human rights; military history and heroes (even those 200 years removed from our own daily lives); beloved musicians, poets, athletes, and inventors; celebrated religious holidays and their most evocative imagery. But some stamps are purely decorative-colorful flowers, butterflies and birds, geometric designs-images chosen from the natural world around us. Just as the stamps you choose to buy in the check-out line of your post office speak volumes about you as an individual, so too will the images chosen for next year’s batch of new stamps tell philatelists around the world a good deal about your country. All of these miniature works of art capture an iconic and purposeful piece of our world, be it an object, person, place, event, or even an abstract concept, and convey their meaning and importance to you as the viewer and consumer instantaneously.

Glyptic iconography, or the imagery on cylinder and stamp seals, is, in effect, no different. Clay sealings have the potential to shed light on many aspects of daily life in the ancient world. Each of their physical facets – fronts, backs, even broken sides – can tell us totally different things. As tangible impressions, their backs tell us what type of containers, goods, or architecture they sealed-what sorts of goods were of such value and importance to a society that they needed to be tracked, collated, secured, and monitored. A broken side can preserve a perfect inch or so of the plaited twine used to secure a square of finely woven linen over the mouth of a ceramic jar, revealing ancient manufacturing details on textiles, rope and cordage, even basketry. When studied en masse, the imagery on their fronts can hint at how far a society’s reach extended beyond their borders, how far a motif traveled, or with what lands a group conducted trade. Sometimes the iconography depicted can even tell us exactly which gods and goddesses were most important to a dynastic family, or the mythological stories most near and dear to them. Even the composition of the clay they are made from can be scientifically tested to pin down its origin, helping us determine if they are imports or local products. Like postage stamps, sealings can shed light on economy, religion, art history, chronology, architecture, language, history, the natural world, and all make and manner of ancient material culture.

And just as a postage stamp has the ability to canonize a time and a place for you, so too can a seal or its impression on a clay sealing. Precisely because they are so personal to the individual or group, certain combinations of carving styles and iconography can be virtual calling cards of the civilization — or, some scholars think, even the individual workshop — that produced them. Thus they have come to be valuable markers of chronological development for millennia of ancient history, in civilizations spanning from Egypt to the Far East.

Most of the stories you might have heard about the seals and sealings from the Heit el-Ghurab (HeG) and Khentkawes Town (KKT) sites here at Giza have been from my colleague, Dr. John Nolan, and his research on a very specific type of cylinder seal. We call these “formal” or “Official” seals, because they often provide titles of officials working during the Old Kingdom, and as such, they are crucial for understanding bureaucratic development. Official seals always include a serekh with the name of the king that reigned when they were carved, making them extremely valuable as chronological evidence. But if you were to take the HeG or KKT site, bisect it vertically and pull the two halves apart to have a look inside, John’s Official seals would be only one of several different carving traditions or threads that flow through the glyptic activity at the site — only one part of the overall weave. I’d like to tell you a bit about one of those other types.

Informal vs. Formal

In 1868, a man named Owen Jones wrote an influential book in England called The Grammar of Ornament. In a nutshell, it gathered together a visual explanation of that which was most characteristic about the decorative arts of many parts of the ancient world – the ornament that was most Egyptian, most Greek, most Persian, Assyrian, Byzantine, Turkish or Pompeiian. He created this grammar by selecting “a few of the most prominent types in certain styles closely connected with each other” and then determining “which certain general laws appeared to reign independently of the individual peculiarities of each” (1868: 1). It is not a “grammar” in the linguistic sense at all, but rather an artistic one, laying out the general laws of what is to be most expected in terms of color, form, motif, and canon of proportion for which society. (Subsequently it became a valuable source book for choosing what particular sort of, say, arabesque was most appropriate for an late 19th century decorative artist stenciling a Moorish room in a Queen Anne Victorian home, and still today, what the proper proportion might be for an acanthus leaf frieze in the dining room of a Greek Revival restoration, even as far west as my Arkansas hometown.)

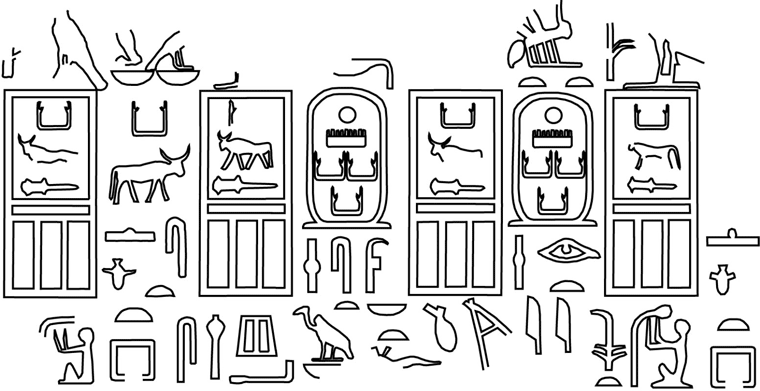

It is with precisely this usage of “grammar” that John and I approach the differences between our “formal” and “informal” seals and sealings. When you have only a small piece of an overall design, which is our situation most of the time, it can sometimes be difficult to categorize them – so in some ways, we use a sliding scale or continuum, moving back and forth between the most Official seal and the most, well, un-Official one. At one end, we have the predictability of the majority of John’s seals – serekh, panel of titles, serekh, panel of titles, and so on, sometimes with a bit of text above and a bit of text below, sometimes a cartouche thrown into the mix – the way the glyptic artists divided the space of the seal is rigid and formulaic, making for a strict and very formal grammar. These seals were carved by talented lapidary artists working at the top of their game, maybe even artists working for the royal house.

An early sketch of one of John’s theoretical reconstructions from an Official seal active at the HeG site – odds are it was carved on a cylinder only about 2 cm in diameter.

But the seals on my end of the spectrum? Well now they’re a totally different ball game.

Stay tuned for the next installment….