Latest News

Congratulations to our team on a successful 2017 season!

The 2017 Giza season consisted of an intense six weeks of study and ‘stock-taking’ in our Giza Lab.

The 2017 Giza season consisted of an intense six weeks of study and ‘stock-taking’ in our Giza Lab.

- The ceramics team (Mahmoud el-Shafei and Aisha Mohammed) studied materials from relatively recent excavations – the 2012 work in Khentakawes East area, and 2015 work in AA South. Over four weeks they were almost able to catch-up on these analyses, and put the finishing touches on their reports for those areas.

- Manami Yahata, who excavated in the Soccer Field West House Unit 1 area several years ago, has always been interested in the large quantities of roofing materials from this house, and because we had a study season, she was able to conduct analyses of these remains, recording the various different types of impressions from logs, branches, matting etc found in anonymous-looking lumps of sandy-mud!

- Ali Witsell, one of our sealings specialists, joined us for a week to make an assessment of what will be needed in the future to complete the analyses of our sealings material.

- Samar Mahmoud, a field-school student in 2015, is studying lithics as part of her Masters program, and was able to join us for a few days a week. She looked at materials from much older excavations, in the Main Street East area (2006-2007), in which large quantities of the debris of stone-tool production were discovered.

- We continued our mission to train young Egyptian archaeologists this season; Essam Ahmed, a student-botanist from the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation (NMEC) was assigned to us as a trainee in Archaeobotany.

- We were also joined by Sarah Hitchens, a PhD student at the University of Liverpool who is making a study of our textile-production tools.

- Dr. Claire Malleson oversaw the BIG job of the season, which was to undertake a huge inventory and stock-take of all the materials stored in our lab. After 29 years of excavations we have vast quantities of ceramics, stone tools, artefacts, faunal remains, archaeobotanical remains, charcoal, sealings, shell, plaster fragments, human remains, and industrial ‘waste’ materials stored in our workroom/Lab on the Giza Plateau. In order to move forward with our research on the lives of the people living in the Heit el-Ghurab and Khentkawes towns it has become very important to properly assess just what we have, what needs to be studied and what has been studied in the past. Over 6 weeks Sarah and Claire, working with our two long-standing Egyptian lab assistants, listed over 14,000 bags of lithics, 5000 bags of faunal remains, 3000 botanical samples, 3000 bags of charcoal, 70 boxes of painted plaster, 200 boxes of shell, remains from 400 human burials, 100 bags of industrial waste material samples, and 100 boxes of roofing material impressions. In most cases the materials we inventoried have never been studied (for example, over 3000 botanical samples have been studied in the past, and we recorded 3000 which are awaiting study).

This season has served as a very useful reminder of the crucial importance of study seasons in archaeology. It can take just 5 minutes to dig and 30 minutes to record a deposit. But it can take many weeks and many different people to analyze the material from that deposit. Without study seasons, it is impossible to keep up!

Happy holidays from AERA!

From excavating Egypt’s ancient cities to training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists, 2016 has been an exciting year for AERA:

- We continued excavations at the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders on the Giza plateau, this year focusing on the office-residence of a high official.

- We began the process of getting our Sphinx data online and publicly available in 2017. This data is from the only systemic survey and architectural study of the Great Sphinx ever done and includes over 8,000 documents.

- We continued our work with the Glen Dash Foundation survey at the Great Pyramid, focusing on the marks left by the ancient builders that offer insight into their building methods.

- We entered the second year of our USAID funded project to develop Egypt’s cultural heritage infrastructure at the ancient city of Memphis, bringing back to life this once-great city, Egypt’s capital through much of Pharaonic history.

- We’re completing work on a walking circuit for Memphis visitors, adding seven new sites to the one currently open and producing guide books, signage, a museum catalog, and other informative materials for visitors.

- We’ve trained 46 Egyptian field school students at two field schools, helping to build the future of Egyptian archaeology.

In 2017, we hope to continue advancing archaeological research and conservation in Egypt, while promoting cross-cultural and educational exchange, training, and support for young Egyptian archaeologists. All of our work is made possible thanks to the support of our members. Join our adventure of discovery. Become an AERA member and help us explore further.

Thank you to our members and the outstanding team who make our research and training possible. We look forward to continuing the adventure with you in 2017!

Thank you to our members and the outstanding team who make our research and training possible. We look forward to continuing the adventure with you in 2017!

Sincerely,

Mark Lehner

President, Ancient Egypt Research Associates

Our members help make possible our excavations in Egypt, field school training, rescue archaeology, conservation, education and outreach. Members also receive printed copies of AERAgrams and annual reports as soon as they are published. Help us keep our field programs vital and effective by becoming a member or giving a gift membership, by donating to AERA or by directly sponsoring an area of research through our giving catalog. AERA is a 501(c)(3) tax exempt, nonprofit organization. Your membership or donation is tax deductible.

Another Piece of the Pedestal Puzzle

This pedestal, found tucked in a closet in the courtyard of the AA-S house, is the best preserved example we have found to date. 3D image created by Kirk Roberts

Ever since we uncovered the first pedestals on the Heit el-Ghurab (Lost City of the Pyramid Workers) site, we have puzzled over their function. The first pedestals were found in 1988 in what came to be known as the Pedestal Building and had tops that were completely eroded and revealed little about their purpose. Eventually we concluded that they probably supported some sort of storage device, such as a bin that straddled the space between two pedestals.

Since that initial discovery, we’ve found many more pedestals in various configurations: both large groups & small sets, in closets & out in the open, isolated & aligned in rows in institutional structures — but always with a gap, or slot, between pedestals.

One big clue to the pedestals function came in the 2006-2007 seasons when we discovered a row of pedestals at the southern end of the Pedestal Building with low mud partitions on top that appeared to define where bins may have rested. In front of some of the slots between the pedestals we found beer jars propped upright at the gaps, as if positioned to catch drips from whatever was stored above or perhaps to serve as standard measures for doling out the contents.

Another clue to the function of the pedestals comes from the many “peg and string” sealings discovered in the vicinity of the Pedestal Building. These sealings could derive from opening and closing the peg and string locks on the chests that may have straddled two adjacent pedestals.

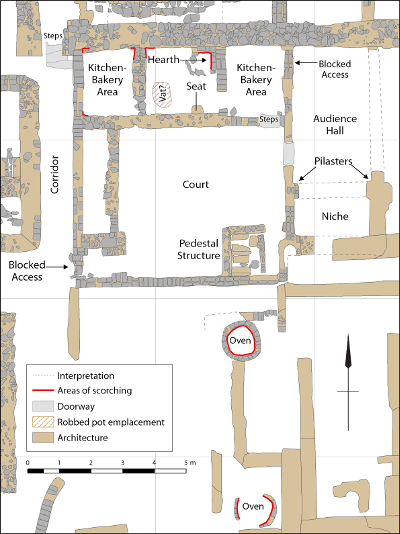

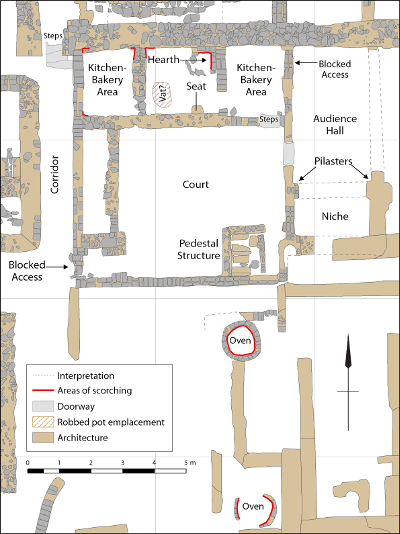

The AA-S area showing the location of the pedestal structure, depicted above.

Then, in 2015, we discovered the best preserved example of a pedestal to date in the AA-S area, just south of the Pedestal Building, which has provided even more tantalizing clues. This entire pedestal structure was meticulously maintained with repeated repairs to the thick plaster. This layout assured that no one standing outside the pedestal closet could see the pedestals or observe whatever might be withdrawn from containers on them, especially if the walls were full height. This emphasis on cleanliness and privacy suggests that the stored goods were best kept in a clean, dry environment and perhaps needed to be secured or hidden from view.

In AA-S we also discovered that a variety of goods were stored above the pedestals, which required different types of containers to hold their contents below. Here, instead of jars, we found a large bowl and a hole that probably once held another bowl in front of the slots. These bowls may have supported baskets or skin bags, which could be filled with dry commodities or liquids stored above that drained into them, allowing a worker to ladle the substance into another vessel. This is in contrast to two other damaged pedestals we also found in 2015 in the building just to the west, where we again found jars positioned at the slots.

We’ve documented the well-preserved AA-S pedestal by using photogrammetery to create a 3D image of the entire pedestal structure. You can download an interactive 3D PDF of this image which will allow you to zoom in and rotate the image and see for yourself how it may have functioned.

Download a 3D PDF of the AA-S pedestal here.

If you browser cannot display the 3D PDF, try downloading the PDF & opening it directly in Adobe PDF Reader.

More information on the Heit el-Ghurab pedestals has been published in our newsletter:

AERAGRAM Vol. 16, no. 2: “Official’s House Emerges in Season 2015” (currently only available to AERA members)

AERAGRAM Vol. 15, no. 1/2: “A Return to Area AA: Informal Seals and Sealings of the Heit el-Ghurab”

AERAGRAM Vol. 8, no. 2: “Enigma of the Pedestals: 2006-2007 Season”

Watch “Unearthed: Dark Secrets of the Pyramids” on Science Channel

In this new Science Channel documentary, AERA’s Mark Lehner and Glen Dash discuss their most recent survey work at the Great Pyramid of Giza and the system of blocks and grooves within the pyramid used to protect the King’s Chamber from tomb robbers.

In this new Science Channel documentary, AERA’s Mark Lehner and Glen Dash discuss their most recent survey work at the Great Pyramid of Giza and the system of blocks and grooves within the pyramid used to protect the King’s Chamber from tomb robbers.

Watch a trailer and read more about the documentary on LiveScience, catch it this month on the Science Channel.

Happy Holidays from AERA!

AERA’s work is made possible thanks to the support of a science-minded community of interest in ancient Egypt. Join our adventure of discovery. Become an AERA member and help us explore further.

From excavating Egypt’s ancient cities to training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists, 2015 has been a great year for AERA.

- We continued our excavations at the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders on the Giza plateau, uncovering two new administrative houses.

- We received a two-year USAID grant to help develop Egypt’s cultural heritage infrastructure at the ancient city of Memphis.

- We celebrated the tenth anniversary of our field school program in Egypt.

- We trained 46 field school students at three different field schools, helping to build the future of Egyptian archaeology.

At AERA, we use the unique archaeological opportunity we have at Giza to lead in archaeological training and cultural exchange on a scale that would not be possible within a large institution. We see the light of a future generation of Egyptian archaeologists, saving and presenting their own deep cultural heritage and becoming part of a new and better horizon for Egypt and the entire region. Help us make this a reality.

Thank you to everyone who helps us make our research and training possible. We look forward to continuing the adventure with you in 2016!

Thank you to everyone who helps us make our research and training possible. We look forward to continuing the adventure with you in 2016!

Sincerely,

Mark Lehner

President, Ancient Egypt Research Associates

Our members help make possible our excavations in Egypt, field school training, rescue archaeology, conservation, education and outreach. Members also receive printed copies of AERAgrams and annual reports as soon as they are published.

Help us keep our field programs vital and effective by becoming a member or giving a gift membership, by donating to AERA or by directly sponsoring an area of research through our giving catalog.

AERA is a 501(c)(3) tax exempt, nonprofit organization. Your membership or donation is tax deductible.

AERA in Scientific American & Smithsonian Magazines

AERA’s work at the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders (also known as Heit el-Ghurab) is featured in the cover story of the November issue of Scientific American. This in-depth article discusses our recent work at the Lost City and how the construction of the Giza pyramids ultimately led to the creation of a social organization that changed the world.

AERA’s work at the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders (also known as Heit el-Ghurab) is featured in the cover story of the November issue of Scientific American. This in-depth article discusses our recent work at the Lost City and how the construction of the Giza pyramids ultimately led to the creation of a social organization that changed the world.

Buy the current issue or read an excerpt online.

An article in the October issue of Smithsonian Magazine examines how the recent discovery of a port of Khufu at Wadi el-Jarf on the Red Sea coast helps to illuminate our own work on the Giza plateau.

Read the full text of this article online.

2015 Area AA-South: Preliminary Results

This year we returned to area AA-South, which is just just south of the Pedestal Building. We were on the lookout for evidence of beer brewing, but instead we found a large structure, which was probably an official residence, that is, an office and residence. What did this house’s residents administer? We still think it included brewing, but we are certain that production in this area including baking.

At the beginning of the season, we hypothesized that two circular mudbrick burnt-red structures in the south served as sockets for the large vats in which brewers heated malt soaked in water. Instead, these circles turned out to be ovens used for baking bread and three rooms in the north of the house served as kitchen/bakery areas. The second room featured a hearth, lined with broken stone and mudbrick, built into the northeast corner. An upside down bread mold formed a corner post, just as we have seen in hearths at other bakeries in the Heit el-Ghurab site. Bakers used these corner hearths for preheating the bread molds. A hole in the floor of the southwest corner of the chamber must have once held a dough-mixing vat. A worn, rounded, limestone boulder against the southern wall allowed someone to sit and turn left to reach into the vat, or right to stoke the hearth.

At the beginning of the season, we hypothesized that two circular mudbrick burnt-red structures in the south served as sockets for the large vats in which brewers heated malt soaked in water. Instead, these circles turned out to be ovens used for baking bread and three rooms in the north of the house served as kitchen/bakery areas. The second room featured a hearth, lined with broken stone and mudbrick, built into the northeast corner. An upside down bread mold formed a corner post, just as we have seen in hearths at other bakeries in the Heit el-Ghurab site. Bakers used these corner hearths for preheating the bread molds. A hole in the floor of the southwest corner of the chamber must have once held a dough-mixing vat. A worn, rounded, limestone boulder against the southern wall allowed someone to sit and turn left to reach into the vat, or right to stoke the hearth.

The most tantalizing find in this area though was another audience hall, with pilasters and a southern niche, similar to the pilaster-and-niche chamber that we found this year in Standing Wall Island. This find substantiated our hypothesis that in AA-S we were excavating another official’s house.

This discovery of yet another large house adds to a picture of the houses of prominent people as organizing nodes of the Heit el-Ghurab proto-city. High-status administrators probably had their houses built as the first, core structures of the neighborhood. These houses served as their official residences and offices when they came to Giza to be on the job at the site of the royal building works.

The level of preservation in this part of the site is excellent and we were able to identify staircases, blockings, and wall decorations. In one room, a black band projected forward from pink mortar just above. These bands probably belonging to a dado, once topped by strips of red and white, similar to images depicted in tomb scenes of domestic settings, for example, in the scene of Wa’etetkehthor and Mereruka on their bed.

Thank you to all our members for helping to make this season possible. We look forward to returning to this area in 2016 to further investigate this house and its surrounding neighborhood to see what else we find!

Reflectance Transformation Imaging of Objects in Giza

RTI specialist Sarah Chapman at work in the lab photographing the Horus amulet seen below

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) is a technique that lights an object from many different directions to better bring out surface detail and create an interactive 3D image. To produce an RTI image, a specialist takes a series of digital photos of the subject with a stationary camera. For each shot, light is projected from a known direction, resulting in a set of photos with different highlights and shadows. RTI software then synthesizes the lighting information to create a mathematical model of the surface of the object.

Once the data is processed the image can be opened in a RTI vieweing software, allowing researchers to re-light the object interactively with “virtual” light from any direction. Computations carried out by the RTI software enhance shape and color attributes, allowing the researcher to see detail not seen with direct observation. Additionally, RTI software can produce 3D imagery that allows a viewer to rotate an object 360°.

This season, RTI specialist Sarah Chapman of the University of Birmingham, UK, introduced AERA to RTI and its potential by photographing objects and sealings from our storeroom in Giza. The minutely detailed imagery she produced allowed our sealings specialist, Ali Witsell, to work on this season’s sealings from her home in the United States. To learn more about this season’s RTI work, please see the article in AERAgram 16.1.

AERA’s Field School Celebrates 10 Years in Egypt

On March 21st, AERA celebrated the 10th anniversary of our field school program in Egypt with a party at the AERA-Egypt Center in Giza. Many of our graduates attended the celebration alongside current students, staff members, and officials from the Ministry of Antiquities.

We wish to thank the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, USAID, The American Research Center in Egypt, and The American University in Cairo for their generous support and co-operation over the past ten years. We look forward to celebrating another ten years of training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists in 2025!

Dr. Mark Lehner speaks at the field school anniversary party (l); current and former AERA staff members, students and instructors celebrate at the anniversary party. (r).

The Pig and the Chicken in the Middle East

A chicken on a limestone fragment found by Howard Carter in front of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Sometime around 1000 B.C.E. pig use in the Middle East declined and was subsequently religiously prohibited. Around the same time that pork fell out of favor, chickens were introduced into the area.

AERA Chief Research Officer Dr. Richard Redding’s paper examining the historical reasons for the decline of the pig (and the rise of the chicken) has been featured in the Smithsonian and the New Historian.

The full text of his article, The Pig and the Chicken in the Middle East: Modeling Human Subsistence Behavior in the Archaeological Record Using Historical and Animal Husbandry Data, is available in the Journal of Archaeological Research.

Abstract: The role of the pig in the subsistence system of the Middle East has a long and, in some cases, poorly understood history. It is a common domesticated animal in earlier archaeological sites throughout the Middle East. Sometime in the first millennium, BC pig use declined, and subsequently it became prohibited in large areas of the Middle East. The pig is an excellent source of protein, but because of low mobility and high water needs, it is difficult to move long distances. While common in sites, the pig is rarely mentioned in texts. In contrast, the use of cattle, sheep, and goats is extensively documented. In the human subsistence system of the arid and semiarid areas of the Middle East, the pig was a household-based protein resource that was not of interest to the central authority. Sometime in the late second or first millennium BC, the chicken was introduced into the Middle East. The chicken is an even more ideal household-based protein resource and, like the pig, is rarely mentioned in texts. In arid and semiarid areas of the Middle East, the pig and the chicken compete for food and labor in the human subsistence system. I hypothesize that in arid and semiarid areas of the Middle East, the chicken largely replaced the pig because the chicken is a more efficient source of protein, it produces a secondary product, the egg, and it is a smaller package; hence, a family can consume one in a day or two. This made the pig redundant and available for use in other human systems. The pig, however, never disappeared from the diet of humans in the Middle East.

The full article is available in the Journal of Archaeological Research.