Latest News

Season’s Greetings from Giza

Wishing you Happy Holidays and a prosperous and peaceful New Year

from the whole AERA team

From exploring Egypt’s ancient cities to training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists, AERA’s work is made possible thanks to the support of our members.

We need your help to explore further.

The AERA team devoted much of 2014 to bringing together 40 years of information to create new reconstructions of the pyramid builders’ urban architecture and water transport infrastructure. Now we look forward to 2015. In eight weeks we begin new excavations and an international field school at the Lost City of the Pyramids.

AERA’s accomplishments are possible thanks to the support of a science-minded community of interest in ancient Egypt. As a member of that community, you make possible AERA’s discovery and training on a scale that would not be possible within a large institution.

Using our unique opportunity at the Giza Pyramids for field research, AERA continues to lead in archaeological training and cultural exchange. While reconstructing the past, we also establish relations throughout contemporary Egypt at a grassroots level to help build a future for Egyptian archaeology.

Help us keep our field programs vital and effective. Think of us in your year-end giving by donating to AERA, giving a gift membership, or by directly sponsoring an area of our research through our giving catalog.

Thank you to everyone who helps to make our research possible!

Sincerely,

Mark Lehner

President, Ancient Egypt Research Associates

View the First Photos Taken from the Great Pyramid Summit

The animation below shows the first photograph taken from the summit of the Great Pyramid, a stereoview photo taken by E.L. Wilson in 1882. This photo also provides the first photographic record of the site where the Lost City of the Pyramids settlement (Heit el-Ghurab) lay buried under 2-6 meters of sand, not to be discovered until Mark Lehner and the AERA team began excavations in 1988.

Download a copy of AERAgram 14.1 for more information and become a member today to receive future AERAgrams and help support our work in Egypt.

New Angles on the Great Pyramid

by Glen Dash

(An excerpt from AERAGRAM 13.2)

No monument in the world has given rise to more speculation about its meaning than the Great Pyramid of Khufu. It has been said to encode “God’s unit of measurement”— the Pyramid inch—to physically represent the mathematical constant pi, and incorporate the Golden Section. Sir Isaac Newton thought it could be used to refine his theory of universal gravitation. All of these ideas, sensible or not, depended to one degree or another on knowing the exact size and orientation of the Great Pyramid. It is surprising then to find that there has been no final, definitive work on the subject. The reason is due, in large part, to the condition we find the Pyramid in today. We find scant traces of its original corners. The best we can do is to project their original positions from the fragmentary data that does remain. It has proven to be a challenge. After Mark Lehner and David Goodman measured the base of the Pyramid in 1984, they set the data aside while Lehner undertook the decades long task of uncovering and mapping the Lost City of the Pyramids. I now return to it.

David Goodman surveys in 1984 with a theodolite and electronic distance measuring device to establish the Giza Plateau Mapping Project grid, looking toward the Great Pyramid. Photo by Mark Lehner.

Goodman, a surveyor then with the California Department of Transportation, established the survey grids now used to map both the Giza Plateau and the Valley of the Kings. For this study, he first laid a survey line along each side of the Pyramid between the bronze survey markers left by [Royal Astronomer and surveyor David] Gill, to serve as a control. Lehner then walked along the survey lines, choosing points to measure. When he chose a point, Goodman recorded its distance from one of Gill’s markers electronically. Goodman then sighted along the survey line using his theodolite’s telescope. Lehner laid a tape measure from the point he wished to measure to the survey line, while Goodman, who could see the tape measure in his telescope, recorded the distance between the two. Surveyors refer to these offset measures as “fallings.” At each station, Lehner carefully noted the condition of the edges of the casing and platform stones. Mapping those points where he found the top, outer edge of the platform stones or the lower edge of the casing stones well preserved, I can attempt to reconstruct the original lines of the Pyramid. While previous surveyors had concentrated only on the casing, Lehner measured the platform as well.

In order to analyze this data, I first need to place it on a master grid. The grid I will use is the Giza Plateau Mapping Project (GPMP) control network that was established by Lehner and Goodman in 1984 and 1985. It assigns every point on the plateau coordinates, like addresses for houses on a city map. The origin of the map lies at the calculated center of the Great Pyramid, and everything is measured from that point, in units of meters. Once the Lehner-Goodman data is converted to GPMP coordinates, I can use a standard statistical method known as linear regression analysis to “best-fit” lines to it…

Read this article in its entirety with data charts and visuals, as well as the other featured articles in our AERAGRAM newsletter.

AERA Archives Officially Registered

The AERA Archives are now officially registered with the Library of Congress, recognized as archives and special collections libraries. As part of the registration process, our Boston and Giza Archives were given special MARC Organization Codes, which are used to represent names of libraries and other kinds of organizations that need to be identified in the bibliographic environment.

These codes are an essential reference tool for systems reporting library holdings, and for those who may be organizing cooperative projects on a regional, national, or international scale. With this recognition, the AERA Archives can be compatible with other library catalogs, making our material accessible when it is open to the public.

Under the direction of AERA Head Archivist Megan Lallier, MLS, our Archives are responsible for ensuring institutional accountability, and for enhancing access to the resources in its care by appraising, acquiring, organizing, describing, making available, and preserving the records of the organization and related documentary materials.

The Archives’ mission is to document the goals and activities of AERA and its contribution of insight and understanding of cultural evolution in Egypt, serving as a primary source of evidence for over 30 years of archaeological investigation in Egypt and as a resource of international significance. The Boston Archive contains originals of over 7,000 drawings including the only scale maps of the Sphinx, approximately 175 linear feet of excavation and specialist data, over 350 notebooks, as well as historic stereoviews, postcards, and photographs. Assistant Archivist Rana Morgan oversees the Giza Archive, which serves as a clearing house for records directly from the field, containing duplicates of all originals to provide access to current and former AERA team members working in Egypt.

Looking ahead, the Archives will be a central component to the intellectual life of AERA, upholding and exemplifying quality, professional access and service to all users while preserving and celebrating its history. Our collections and services will facilitate growth, research, and understanding of AERA and its projects, and will document and highlight its contribution of insight and understanding of cultural evolution in Egypt.

AERA Archaeologist Shares 3-D Scanning With Global Audience

Kyoto, Japan – On September 16th, Kyoto University hosted a one-day event where 22 individuals shared their knowledge and experience in a wide variety of innovative ideas and practices. The event, TEDxKyoto, designed to inspire the world as presenters shared their passion and success within the areas of technology, entertainment and design (TED).

Among the presenters was Yukinori Kawae, an archaeologist specializing in 3D survey. Yukinori has worked with AERA since 2006 with the launch of our Giza Laser Scanning Survey (GLSS). Using two laser scanners and one laser range finder, Yukinori and his team of surveyors produced detailed three-dimensional model images of monuments such as the tomb of Queen Khentkawes and the Step Pyramid of Saqqara. These images showed all archaeological features such as each stone of the masonry and bedrock fissures and strata. You can read more about GLSS and Yukinori’s work on the Step Pyramid in our GOP 3 and GOP 4 publications.

TEDxKyoto was planned and coordinated within the Kyoto community and independent from TED, a nonprofit organization devoted to “Ideas Worth Spreading”. The TEDx program gives communities, organizations and individuals the opportunity to stimulate dialogue at a local level. In the span of its 26-year existence, TED has stayed true to its mission, bringing together some of the most fascinating thinkers around the world and encouraging them to give the speech of their lives. TED speakers have included Bill Gates, Jane Goodall, Sir Richard Branson and former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown. Talks are available for free at TED.com.

To view Yukinori’s full TEDxKyoto presentation (Japanese), click here. English scripts will soon be made available for all Japanese presentations.

Visit the TEDxKyoto Facebook page for an in-depth look at the event, including behind the scenes images and commentary, as well as photos and videos of several presenters.

NOVA/Sphinx Encore Presentation

Be sure to catch an encore broadcast of the Writers Guild Award nominated Riddles Of The Sphinx on NOVA, Wednesday May 18th at 9:00 pm on PBS (check local listings).

This documentary, filmed by Providence Pictures producer Gary Glassman, looks to uncover the truths behind some of the biggest mysteries and theories surrounding the ancient statue, and features AERA Director Dr. Mark Lehner as one of the archaeologists looking for answers.

Riddles of the Sphinx debuted on the PBS science program NOVA early last year. Watch it now on Vimeo.

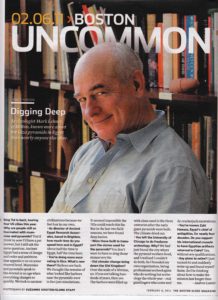

Dr. Lehner Featured in Boston Globe Magazine

AERA Director Dr. Mark Lehner’s brief interview in the February 6th issue of the Boston Globe Magazine. Click on the image to enlarge, or visit the Boston Globe Magazine’s web site at www.boston.com/magazine.

The Wall of the Crow

Heit el-Ghurab

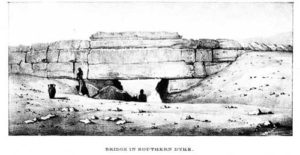

Wall of the Crow gate from Vyse, 1840.

There is a massive, ancient stone wall that stands a few hundreds yards south of the Sphinx. But because it lay partially buried and overshadowed by the pyramids and Sphinx, tourists have hardly noticed it. Known locally as the Wall of the Crow (Heit el-Ghurab in Arabic) it is 200 meters (656 feet) long, ten meters (32.8 feet) high, and ten meters thick at the base.

The Wall is the northwest border of a tract of low desert that we at first designated Area A and later became known as The Lost City of the Pyramids or Heit el-Ghurab (named after the wall’s Arabic name). When we first started our excavations at the Lost City site, we suspected that the Wall of the Crow dated to the Old Kingdom 4th Dynasty (2575-2465 BC), like the Giza Pyramids and the Sphinx, but we did not know why the Egyptians built it. Evidence suggested that they never completed the mammoth undertaking. They never dressed the masonry to produce a finished face to the structure, as was their standard practice with pyramids, tombs, and temple walls.

After further excavations, we can now say for certain that the Wall of the Crow was built as part of our 4th Dynasty (2551-2472 BC) complex and the archaeology has led us to form some ideas as to its function.

Gateway to the sacred?

Wall of the Crow gate.

The great gateway in the Wall of the Crow may be one of the largest gateways from the ancient world. It has been visible for the last 4,500 years and yet very little has been written about it. Once we cleared away a thick, sandy overburden, we discovered what an impressive structure the gate is—2.5 to 2.6 meters wide (about 8.5 feet or five ancient Egyptian cubits) and about 7 meters (23 feet) high. Because the base of the Wall is more than 10 meters thick, the gate is actually a short tunnel. The ancient roadway going through the gate was paved with worn or abraded ceramic fragments and laid out with a subtle camber—the sides slope down and away from the center—a common feature of ancient roads.

Along the length of the south side of the wall east of the gate, we cleared a ramp-like slope on the surface of an embankment of limestone chips. This mason’s debris must have been waste from building the wall. It also may have been used as a ramp to drag the massive lintels up over the top of the gate. After placing the stones, the builders left the debris immediately in front of and inside the gate. Upon this debris, traffic formed a path that slopes down 2 to 3 meters (6.56 to 9.84 feet) from north to south. The path passes through the gate to a broad terrace formed of compact sandy masons’ debris that extends at least 30 meters north of the gate.

Function

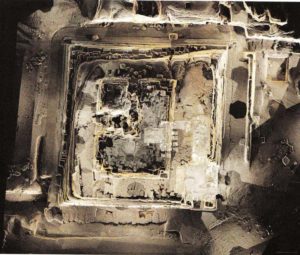

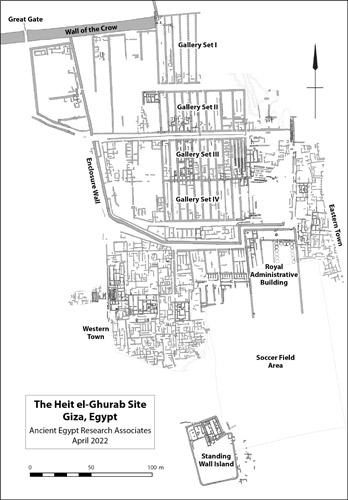

A plan of the Lost City of the Pyramids site. Note the gallery at the east end of the Wall of the Crow.

Why did the builders put so much effort into an immense stone structure that was not part of a pyramid complex nor connected to other structures at Giza? The builders shaped and hauled a huge number of massive blocks to form something more like a dike than a wall. In contrast, the rest of our settlement is mostly built of mud brick or broken stone from the nearby Maadi Formation. The Wall may have separated the sacred precincts of the pyramid plateau from the precincts in which the workers lived. The Enclosure Wall that bounds the Gallery Complex on the west nearly abuts the Wall of the Crow, and the regulated passageways out of the settlement—especially Main Street, the principle axis—led right to the massive gateway in the Wall of the Crow.

In 2002 we found clear evidence that the Gallery Complex (at least Gallery Set I) predated the Wall of the Crow. Until then we were not certain where the Wall ended on the east. The eastern end of the Wall slumped in two layers of large stones, the result of collapse and robbing in late antiquity (we found Late Period burials under the lowest layer of toppled stones). The remains of the gallery walls were about waist to chest-high at the eastern end of the Wall, but about three meters to the east (10 feet), the gallery ruins were cut down to ankle level in a great depression. A massive deposit of granite dust and chips filled this big depression. The granite was from large-scale work nearby, possibly cuttings from the granite casing on the Menkaure Pyramid. But what force cut this depression through the mud brick gallery walls well before the end of the 4th dynasty occupation on our site? Perhaps a flash flood.

Flood control?

Geoarchaeologist Karl Butzer, who studied the environmental history of our site, believes that the 4th Dynasty Egyptians built their settlement on the outwash of a wadi, a stream bed that occasionally carried heavy floods running off the high desert. The Wall of the Crow stands just to the south of the stream bed and could have served to deflect the floodwaters.

East end of the Wall of the Crow.

If the inhabitants built the massive stone wall for protection against desert flooding, why not extend it across the northern end of the whole Gallery Complex? Perhaps they thought that the thick, mud brick northern wall of Gallery Set I could withstand the wadi floods. The Wall of the Crow might then have been meant to protect the western flank of the Gallery Complex. In fact, an earlier settlement here might actually have succumbed to flash floods. In the lowest layers, those predating the Gallery Complex, we found settlement debris—mud bricks, pottery fragments, and limestone rocks—mixed with mud and pebbles washed down from the natural gravel in the high desert. We continue to look for evidence to support a hypothesis that the Wall may have served as flood-control to protect the workers settlement.

Sacred structure

Late Period burials sprawl in a large cemetery across the northwestern portion of our site, with grave upon grave cut into the Old Kingdom deposits. Toward the eastern end of the Wall of the Crow, the graves increase in density like the epicenter of a galaxy.

Burial at Wall of the Crow.

The Late Period (747-525 BC) residents of nearby towns must have considered the area around the Wall of the Crow as sacred ground. The burials extend right up to the east end of the Wall, with some of the dead interred in the sand above rocks that tumbled from the Wall. These burials post-date the collapse of the eastern end of the Wall. Caches of animal bone that we encountered in the same sand layer as some of the nearby Late Period burials are another sign of the Wall’s sanctity. One cache included two skulls—from a bovine and a smaller animal, possibly a goat. Another cache contained two cattle skulls. In the spring of 2000, when we began clearing the southern side of the Wall of the Crow near the east end, we encountered a third cache—a bovine skull and a Late Period amphora tucked into a niche between the blocks of the Wall.

Child burials

Next to the eastern end, the percentage of child burials is higher than in other areas: 60% compared with, for example, 27% in a nearby square. Many of these children were adorned with jewelry and amulets, while adult burials contained no grave accoutrements. We do not yet understand the significance of these special child burials.

The Wall of the Crow today

Archaeologists working at the Wall of the Crow.

The area around the Wall of the Crow is still a burial ground. An Islamic cemetery engulfs the west end of the Wall and a Coptic Christian cemetery lies just south of it. During funerals, the deceased is carried in a procession through the great gate in the Wall. It is possible that this part of our site was a burial ground from late Roman to early Christian times. The first Muslim graves, the tombs of sheikhs (learned Muslim men), were built north of the west end of the wall. Both cemeteries—Coptic and Muslim—have wells; water sources are often associated with sacred traditions.

The Wall of the Crow is also still associated with fertility even today. Until recent years, women hoping for children would squat near a nail (a bronze survey peg pounded into the Wall by a surveyor many years ago), and then walk around the raised limestone blocks seven times. Through the millennia that the Wall of the Crow has laid half-buried, it has maintained its sacred aura and perhaps become even more mystical. We certainly look in awe upon this massive structure poised between the worlds of the living and dead, both ancient and modern.

Feeding Pyramid Workers

The ancient bedja.

How did the ancient Egyptians feed thousands of workers at Giza? We know from ancient texts that a staple diet of bread and beer were disbursed as rations in royal labor projects. What kind of bread did the pyramid builders eat? In September and October 1993, The National Geographic Society funded our experimental archaeology project to help answer this question.

Pyramid builders’ diet

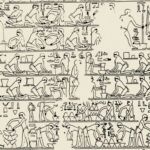

Hieroglyphic texts tell us that Old Kingdom food production and storage facilities fell under an institution called per shena (written with the house and plow signs, roughly translated to “house of the commissariat”). This term indicates a food production establishment that included bakeries, breweries, and granaries. Evidence discovered from Elephantine Island in southern Egypt all the way to Palestine indicates that bread baking in bedja was a common and wide-spread practice for nearly 500 years.

Large, crude ceramic bedja bread molds.

In AERA’s 1991 season we found two bakeries, at that time the oldest known bakeries from ancient Egypt. These bakeries are the archaeological counterparts of the bakeries depicted in many scenes and limestone models from Old Kingdom (2575-2134 BC) tombs.

Fragments of the large, bell-shaped bread pots like those we see in the tomb scenes litter the Lost City in the hundreds of thousands. Labeled bedja in the tomb scenes, the largest weigh up to 12 kilograms each (26.5 pounds). We have found many intact examples at our site as well.

Two Giza bakeries (1991-92)

Mixing vats

At Elephantine Island our German colleagues excavated a bakery in which the bakers allowed the ash to accumulate nearly to the roof. The accumulated ash preserved the columns, about 28 cm (11 inches) in diameter, to their total height of 3.20 meters (10.5 feet).

Hearths and depressions

Tomb scene of bread-baking

In our bakeries, two rows of depressions (looking like oversized egg cartons) had been dug into the floor to serve as receptacles for the preheated bedja. Tomb scenes show a secondary bedja placed upside-down as a cover over the filled bread mold. We think the covers were pots that had been preheated on the open hearth. Hot ashes were probably piled around the two pots to complete the baking process, as suggested by the abundant ash and charcoal fill of the depressions.

Bakery attachment

Archaeologists have found that ancient Egyptian food production facilities are generally attached to some kind of household—the household of the king (a palace), the household of a god (a temple), the household of a governor (a manor), or the household of a private person.

The bakeries in A7

The bakeries we found at our site, on the other hand, appear to belong to industrial-scale production. But instead of building for an economy of scale (building one large industrial-capacity bakery) the Egyptians built many household-sized bakeries near each other. This fits in many ways with the kind of social structure that permeated all of ancient Egypt. Most production was done on a household level: cooking, pottery making, agriculture, metal working, and textile manufacturing, etc.

Ancient Egyptian households typically had a variety of specialized work spaces attached to them: granaries, bakeries, butcheries, weaving, carpentry shops, etc. The inhabitants of this pyramid city seem to have reached for large-scale production by enlarging bread molds and replicating household production facilities many times over. These bakeries were certainly part of a large, specialized production center—a state institution of the royal house.

We have here the clearest physical example of the kind of state (or estate) bakery labeled as per shena, like that in the tomb scenes of the 5th Dynasty official, Ty, at Saqqara. We found a possible corrupt writing of per shena etched crudely on a sherd (pottery fragment).

Use

It is interesting to note that apparently, as the inhabitants used the bakeries, they allowed them to simply to fill up with ash. By the final days of the bakery, the ash filled each room to the brim of the vats.

At Elephantine Island our German colleagues excavated a bakery in which the bakers allowed the ash to accumulate nearly to the roof. The accumulated ash preserved the slender, wooden columns, about 28 cm (11 inches) in diameter, to their total height of 3.20 meters (10.5 feet).

Fuel

Egypt is a desert country that does not have large forests to provide wood for fuel. Although wood was an expensive resource, the Old Kingdom Egyptians seemed to have burned it with abandon at Giza for a variety of purposes. Cooking and baking bread on the scale that the Egyptians were doing at the Lost City would have required a constant supply of fuel. The fuel was mostly acacia, which grew naturally across a wider area of Egypt along the low desert.

Stack heating replica bedja over a fire.

Some of the acacia may have been prepared as charcoal before being transported to Giza, as charcoal is much lighter than wood and therefore easier to transport. Even if this was the case, the builders of the pyramids were also burning wood to make gypsum to use as mortar for construction and to make and harden copper tools. We extracted small samples of gypsum out of the Giza Pyramids themselves in order to do radiocarbon dating in 1984 and 1995.

The ancient builders were probably also consuming vast amounts of acacia, which produces a hot fire, for the preparation of copper tools. Indeed, they may have amassed the largest concentration of copper tools anywhere in the world during the third millennium BC because of all the tools need to build the giant pyramids.

In a settlement the size of the Lost City, there must have been an almost permanent haze of cooking smoke across the low desert below the pyramids. Altogether we can say that between cooking, making mortar, and working metal, the Lost City was a thermodynamically expensive site: the inhabitants burned a lot of resources to produce food and material for pyramid construction.

Experimental archaeology

Recreating the ancient bakery.

The bakeries we found at Giza raised some specific questions:

- Why were the bedja stack-heated prior to baking?

- Did the bedja act like miniature ovens?

- Was ash raked around the preheated pots?

- What kind of bread was ultimately produced?

Experimental technique

Baking in progress.

We discovered that the low walls of the ancient bakery rooms were probably intended to be low and flat, providing essential working surfaces, like our modern kitchen work surfaces. Higher walls would have trapped and held all the smoke and ash generated during baking, making the small space intolerable to work in.

Experimental recipe

The emmer wheat and barley available to the ancient Egyptians contained very little gluten, the protein which gives modern breads their light, airy texture. The volume of our bread molds indicates that bread cooked in them must have been leavened.

Dough vats and finished bread.

There is a question about the presence of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) in ancient Egypt, but it is believed the species was not widely in use in Egypt until the Greeks brought it in. Emmer and barley were clearly the staple cereals but bread wheat does turn up occasionally and we have even found a little at Giza (though not enough to say that it was used for bread making at our site).

For our experiment, we leavened our bread with local, wild yeasts captured at Giza by Ed Wood, a retired pathologist, who has devoted much of his life to studying wild yeasts and the sourdoughs made from them. Ed tried various combinations of emmer and barley as described in his book World Sourdough Breads from Antiquity (Ten Speed Press, 1996).

Experimental results

We found that the bread baked best when covered with a preheated bedja, as shown in ancient tomb scenes. Without the cover, the bread did not bake through all the way.

It is possible, however, that we made the bread mold walls too thin and that the scenes depicting pots stacked over fire are actually showing a process to temper the pots to effect a non-stick surface or perhaps they were even firing the ceramics.

We think that the pots were set into the depressions and surrounded by charcoal. Then the bakers would light straw tinder around the pots. This might explain the greenish-gray accretion on the outsides of our ancient bread molds. We analyzed the accretion as vitrified phytoliths, the siliceous inclusions in plants and grasses.

Experimental taste test

Ed Wood and the experimental bread.

Experimental future

AERA patron, Dr. Nathan Myrhvold (physicist and master chef) is also interested in ancient breads and baking techniques. It is very clear from ancient depictions that the dough was poured into the bread molds. Nathan thinks that perhaps the dough was more like a biscuit or muffin batter than a spongy dough. We are looking forward to more experimental archaeology in ancient culinary arts. We would like to recreate the bakeries again to better answer some of the questions that are so important to understanding the diet that sustained the builders of the pyramids, because it is on just such basics of everyday life that great civilizations—and pyramids—were built.

Like so many issues surrounding the Giza Pyramids, it is often the little details, like how the ancient bakers made bread and fed thousands of workers, that are most important in understanding pyramid building and the most fascinating questions to us as archaeologists.

Searching for a City

Where do you look for a lost city?

The Giza Plateau, Egypt

AERA’s search was helped by eliminating any areas where the ancient Egyptians would NOT have built their pyramid settlement.

The Pyramids are surrounded by other monuments of the Old Kingdom (2575-2465 BC) that restrict the available space on the Giza Plateau:

- Pyramid temples, causeways, and valley temples once extended east of all three pyramids.

- Queens’ pyramids sit on the south and east sides of the Menkaure and Khufu pyramids respectively.

- Huge mastaba tombs stand east and west of Khufu’s pyramid.

- The Khufu quarry lies southeast of Khafre’s pyramid, south of his causeway and north of Menkaure’s causeway.

Petrie’s barracks

Khafre galleries: barracks or storage?

Petrie carefully described the composition and dimensions of the galleries, which are 30 meters (98.4 feet) long and 3 meters (9.8 feet) wide, extending from a back western wall of an enclosure 400 meters (1312.3) long and 85 meters (278.8) wide. He noted “many fragments of statues were found, in diorite and alabaster, of the fourth dynasty style: and among a large quantity of quartzite scraps lying on the surface…part of a life-size head.” (The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh, Petrie, 1883).

Royal statue fragments might be out of place in a workman’s barracks and Petrie described no cultural material that would indicate the domestic life of a barracks.

Giza Plateau Mapping Project excavations: 1988-89

In order to test Petrie’s hypothesis, which had been accepted by Egyptologists for over 100 years, we proposed to re-excavate Petrie’s barrack galleries along with two other areas at Giza to look for evidence of a pyramid-age settlement.

Using our GPMP survey control network, surveyor David Goodman ran three north-south lines along the 30 meter wide (98.4 feet) barrack structures, creating front, back, and middle divisions. Then we opened about 11 excavation squares in the front, middle, or back of the galleries.

Evidence of craftwork

The galleries

Near the entrances of one gallery we found fragments of figurines: lion figurines, a small statue of a king, and what looked like possible models of larger architectural pieces.

We found rear portions of the galleries nearly empty. If workmen had been living, cooking, and sleeping in these galleries for decades, we would expect to find the kind of settlement debris so common wherever people lived in ancient times: pottery, ash, bone, and other refuse.

The figurines, along with pieces of copper, malachite, and feldspar, were evidence of craft working, leading us to the conclusion that Petrie’s barracks were not barracks at all.

A royal figurine.

The material we found suggests that at least parts of the galleries were used as a craft production area. But the overall structure is huge. Other galleries may have been used for storage, perhaps even grain storage, though we didn’t find good evidence for grain.

Alternatively, most of the galleries may have been left empty, a state administrator’s idea that never took final form. The galleries may have served as symbolic storage for the pharaoh’s afterlife like the vast underground galleries west of the Step Pyramid complex at Saqqara, and they may never have been used at all.

So if Petrie was wrong, where did the ancient pyramid builders live?

(For more on the Khafre galleries, see Lehner and Conard, Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, XXXVIII, 2001.)

Another settlement location?

Mark Lehner had proposed another possible settlement location (see MDAIK 41, 1985)—but while initially promising, Area B quickly proved an unlikely location.

Area B is a broad elevated bowl on the Maadi Formation due south of the Great Pyramid. Karl Kromer excavated the northeastern part of the bowl (1971-1975), revealing a sizeable dump of settlement debris.

Kromer found seal impressions with the names of Khufu (2551-2528 BC) and Khafre (2520-2494 BC) but none of Menkaure (2490-2472 BC). He was probably right in his assessment that the cultural material was dumped from an ancient settlement that was razed somewhere nearby.

Area C at top, Area A lower left

When we inspected the bottom of the bowl early in the 1988-89 season, we found natural marl clay just below a shallow sand cover. The bowl may have been a quarry for tafla, the buff-colored desert clay that the ancient builders used as plaster and mortar in ramps and embankments.

It’s possible that a settlement once occupied Area B, and that the quarrymen razed the settlement, dumping the material to a far corner as they exploited the bowl for more tafla. It is also possible that the settlement remains derived from an older phase of occupation that the builders removed from Area A.

We therefore decided to focus our efforts on Area A.

A city under the sand

In 1934, Egyptian archaeologist, Selim Hassan excavated test trenches in a patch of low desert extending about 450 meters (1476.3 feet) south of a colossal stone wall called Heit el-Ghurab (Wall of the Crow). The wall is situated some 400 meters (1300 feet) south of the Sphinx. Hassan hit mud-brick walls and pottery in all his trenches, indicating that ruins of a large settlement lay below the thick sand layer that blanked the site.

Hassan’s 1934 results, together with more pottery and mud brick walls exposed when people from nearby riding stables removed the sand cover, led Mark Lehner to propose in his MDAIK article that a major settlement of the 4th Dynasty once thrived south of the Wall of the Crow. We designated this Area A.

The Lost City walls.

We limited our 1988-89 excavation in Area A to five 5 X 5 meter squares (16.4 X 16.4 feet) just at the base of the sandy eastern slope of the Maadi Formation ridge. Every square produced evidence of ancient settlement. The easternmost of these squares (Squares A1, A2, and A4) produced the most promising evidence of a settlement for workers.

We found two buildings in these squares: one building of alluvial mud brick and another of stone and mud mortar, plastered inside with tafla (desert clay).

The late phase of activity in these squares was connected with bread making. We recovered a considerable number of sherds (broken pottery) from large, bell-shaped bread moulds, of the kind called bedja in Old Kingdom scenes. It appeared that these were dumped all at once, suggesting a bakery in the vicinity.

Between the stone building and the mud brick structure we found an alleyway filled with a dense refuse deposit rich in bone, ash, sherd, and a number of clay sealings bearing the name of Menkaure, builder of the third Giza Pyramid. Unlike Kromer’s sealings in Area B, we found our sealings in secure context within a settlement.

The main building, of fieldstone and clay, contained a series of pedestals in two rows separated by a center wall. The pedestals appeared to be the foundations for storage compartments.

A small closet-like compartment in the northeast corner contained three, smaller pedestals. We called this the Pedestal Building. In subsequent seasons, we have found many more of these pedestals in small compartments and in long running rows at various places across the site.

In 1988-89, one old hypothesis had been tested and found wanting: Petrie’s barracks were probably not barracks. Another hypothesis proved to be problematic: Area B might once have contained a settlement but, if so, it was removed in antiquity.

Area A was just beginning to reveal its secrets. The Pedestal Building would prove to be only the tail of a huge archaeological beast: the Lost City of the pyramid builders.